Central Asian countries – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan – have experienced a difficult transition from a shared Soviet past to diverse paths of nation-building and economic liberalization since gaining independence in the early 1990s. Since then, the Kremlin, despite China’s and Turkey’s increasing influence, has been behaving as if it owns the region.

However, many experts agree on the theory that after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Moscow’s influence in Central Asia is fading. In contrast to this argument, others say that if we evaluate the diplomatic, military, energy, and economic factors, they can still be classified as “Putin’s Pals.” To get a better understanding, we asked Anton Bendarjevskiy to analyze the situation. Anton Bendarjevskiy is the Director of the Oeconomus Economic Research Foundation in Budapest. He regularly provides expertise on the security policy of post-Soviet states.

War in Ukraine

“The Russian-Ukrainian War affects Central Asia due to the region’s dependence on Russia for security and economic ties, while also instilling a fear of Russian neo-imperialism that pushes leaders toward a »multi-vector« foreign policy,” said Anton Bendarjevskiy.

The so-called »multi-vector foreign policy« in consideration of Central Asia means aiming for balanced relations with Russia and other powers such as China, the Western world, and Turkey.

In the case of Kazakhstan, for example, it means that the country’s leader, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, openly criticized Putin on the war, and Kazakhstan has not recognized the Ukrainian regions occupied by Moscow as part of Russia. Meanwhile, the Astana maintains its economic and security links to Russia.

“While Central Asian states have historically been dependent on Russia for security, the invasion of Ukraine has led them to question Russia as a reliable partner not just militarily but also economically,” added the director of the Oeconomus Foundation.

According to him, “the loss of Russian influence, or at least its erosion, in the post-Soviet region actually started after the capture of Crimea in 2014. Before that, in the early 2000s, Russia was able to offer an attractive economic alternative to the region.

After the occupation of Crimea, the post-Soviet countries like Belarus and Kazakhstan were frightened by such imperialist political ambitions of Russia and increasingly tried to keep their distance from Moscow. The Russian-Ukrainian war has only intensified these processes.”

On April 19, four Russians were detained in Kyrgyzstan for recruiting mercenaries for the Russian army. They included Natalya Sekerina, an employee of the Russia House, a cultural agency with close ties to the Kremlin, and Viktor Vasilyev, part of an information network run by murdered Wagner mercenary group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin.

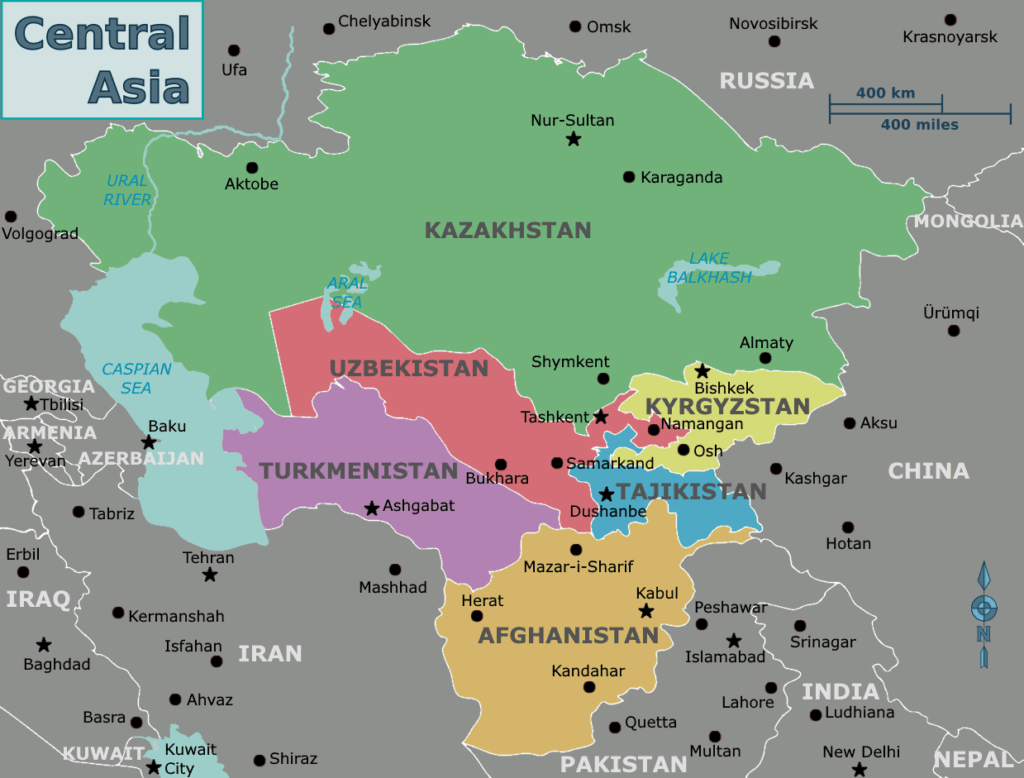

Political map of Central Asia

Source: Wikipedia

In Russia, under the cover of their campaign against illegal immigration, Russian authorities have also snatched migrants off the street and sent them to the frontline in Ukraine, making workers from Central Asia nervous about travelling there to make up Russian labor shortages.

Central Asia’s Economic Maneuvering

The five Central Asian nations are members of one or more of the Russian-led economic institutions: the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Single Economic Space (SES), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and the security organization, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan are members of the CSTO; Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are members of the Eurasian Economic Union; and all of the Central Asian states are members of CIS.

The CIS is a loose association of post-Soviet states, while the Customs Union and the subsequent SES were more specific initiatives by a smaller group of countries—initially Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan—to foster deeper economic integration by eliminating trade barriers and creating common policies,

recalled Anton Bendarjevskiy.

The actual integration processes in the region started in the 2000s, when the CSTO was established. The purpose was to create the foundations for future post-Soviet cooperation. Crimea was a watershed moment in economic cooperation, as the participating countries increasingly viewed this formation centered in Moscow as a threat and preferred to delay further integration efforts, as the expert emphasized.

“After 2015, when the Eurasian Economic Union came to a standstill, Vladimir Putin changed his strategy. He brought out the concept of a Union State. The Russian president had the idea to gradually complete the integration with Belarus, then to extend it to other countries in the post-Soviet space. After Belarus, Kazakhstan, then Armenia, Georgia, and so on,” said Bendarjevskiy.

Now, Russia’s focus on its own economic interests and the resulting financial penalties from international sanctions have weakened its ability to provide economic support to Central Asian nations.

Another major factor keeping the region reliant on Putin’s regime is millions of migrants from the region, particularly from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan—who work in Russia. According to Russian official statistics, there are about 6.1 million migrants in Russia, and most come from the states in the region. Remittances make up 35–40 percent of GDP in Tajikistan & Kyrgyzstan and around 10 percent in Uzbekistan.

Kyrgyzstan, being the poorest country, is the most dependent on these remittances and Russian energy imports. The others have better chances of distancing themselves from the Russian integrational projects. Turkmenistan and Tajikistan are among the cruelest dictatorships in the world; they are also rich in various raw materials. For instance, Turkmenistan has the fifth-largest gas field in the world, with reserves between 13.4 and 13.6 trillion cubic meters.

More recently, China has become the top trade partner for most of them, and Russia remains the second one for Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. The increasing economic influence and investment from China have provided a significant alternative to Russian financial power in the region. China wrapped up its latest engagement effort in Central Asia in June with a 1.5 billion (US$209 million) yuan pledge towards livelihood and development projects in the region, as the South China MP reported.

Irreversible Erosion of Leverage?

Russia’s aggressive assertion of its dominance in the Central Asian region is likely to backfire on Moscow and accelerate this trend. The Kremlin depends on Central Asia in nearly all the ways the region depends on Russia.

Since February 2022, Russia has been unable to simultaneously concentrate on multiple regions.

This was most visible in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, the disputed territory between Azerbaijan and Armenia, where Russian soldiers maintained this frozen state of conflict for decades, which allowed them to influence the dynamics of the region. Eventually, the Russian peacekeepers had to be withdrawn from the region, also as a result of the war in Ukraine. In the end, Azerbaijan was able to retake Karabakh by practically ignoring the Russian military forces there. Now, the US President, Donald Trump, was the one who successfully brokered the peace deal between the parties.

“In the short term, the status quo in the region will not change, but this is a process. Chinese trade became predominant around 2009/10, and since then, this process has only strengthened. After the decline of economic influence, military power is degraded, and then political influence disappears. As we have seen in the case of Azerbaijan, the same scenario could happen in Central Asia,” concluded Anton Bendarjevskiy.