British Prime Minister Keir Starmer occupies a unique position among the “Trump whisperers” of Europe. Although he is far from the President both in personality and ideology, he has been surprisingly successful in forging a close personal relationship with Donald J. Trump – with tangible results for the United Kingdom.

The Labour government under Sir Keir Starmer does not feel the need to walk a tightrope between the United States and the European Union. In the grand British tradition of “having one’s cake and eating it,” Starmer has been resetting relations with Europe while simultaneously deepening ties with the US – so far, with considerable success.

On 31 July 2025, President Donald J. Trump issued a decree imposing the so-called “Reciprocal Tariff Rates,” hitting many countries – including long-standing US allies – quite hard.

A blanket rate of only 10 percent was applied to British goods not previously subject to the already-announced 25 percent tariff on steel, aluminium, cars, and car parts. Meanwhile, no tariffs were imposed on imports of UK services. In contrast, other trading partners now face blanket tariffs of 15 percent or more, with extreme cases like Canada facing a 35 percent levy.

The European Commission, which negotiated on behalf of the EU’s member states, has come under fire from certain European leaders for securing a worse outcome than the UK government.

In British pro-Brexit circles, the reaction has been one of schadenfreude and a sense of vindication for leaving what they view as an ineffectual Union.

It’s a striking reversal from the Brexit years, when the British government was derided as incompetent and the Commission praised as a masterful trade negotiator.

A 10 percent blanket tariff is, of course, not a complete victory for the UK (that would be avoiding tariff hikes altogether), but it is nonetheless a respectable outcome – one that has surprised many.

With President Trump’s state visit to the UK scheduled for September, this article seeks to uncover the factors behind this unexpected success; placing particular emphasis on the surprisingly close personal relationship between Trump and Starmer.

The US-UK Special Relationship in Personalities

The “Special Relationship” between the US and UK may be somewhat one-sided, given the geopolitical dominance of Washington but it is a genuine bond. It is built on a shared language, common values and interests, strong economic ties (more on that later), and a historic alliance dating back to World War I.

This relationship was formed in the 20th century, a period during which the US rose to superpower status and the UK saw a decline in its global influence. As a result, the state of transatlantic relations has often mirrored the personal chemistry between presidents and prime ministers.

There have been famously close pairings: Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, as well as Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush with Britain’s Tony Blair.

Yet history also records friction.

During World War I, Prime Minister David Lloyd George maintained a frosty relationship with President Wilson, which was followed by decades of American isolationism until the alliance of WWII. In 1956, President Eisenhower abruptly halted the Franco-British-Israeli invasion of Egypt – a pivotal moment in Britain’s international decline which led to the downfall of Prime Minister Anthony Eden.

A few years later, PM Harold Macmillan clashed with President John F. Kennedy over the UK’s independent nuclear capabilities (a dispute Macmillan ultimately won). In the late 1960s, PM Harold Wilson refused President Lyndon B. Johnson’s request to send British troops to Vietnam – despite both leaders being from the political Left.

President Barack Obama takes questions during a town hall meeting with an audience from the U.S. Embassy’s Young Leaders UK program in April 2016 (Photo: Lawrence Jackson)

In more recent times, David Cameron had good working relationship with President Obama, but it lacked the warmth of Reagan-Thatcher or even Bush-Blair.

During his first term, Trump had a poor rapport with Theresa May but openly embraced Boris Johnson, whom he famously dubbed “the British Trump.”

Trump’s rhetorical favoritism, coupled with President Joe Biden’s well-known Irish pride – a sensitive point during the Brexit negotiations – likely contributed to Biden’s chilly relationship with Johnson. The chaotic Kabul evacuation in 2021 further strained ties, although Western unity was rekindled after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Britain Through Trump’s Eyes

Trump often highlights his Scottish ancestry and admiration for Britain, particularly for Winston Churchill. Unlike President Obama, who removed Churchill’s bust from the Oval Office due to his blotted colonial legacy in Kenya, Trump restored it with pride during his first term.

He also views the Brexit referendum as a precursor to his own 2016 election victory.

In this context, Starmer’s repeated insistence that the UK will not reverse Brexit—or rejoin the single market or the customs union—may appeal politically and personally for the President.

Which brings us to the issue of political irritants.

The President (incorrectly, it must be said) sees trade imbalances as threats to the US economy and national security.

He apparently weighs them alongside other political considerations, such as how countries regulate US tech firms, buy American energy, handle irregular migration, combat drug trafficking, or treat his ideological allies.

All told, the United States is the UK’s largest trading partner, accounting for 17.8 percent of total British trade. The UK, in turn, is the US’s 5th-largest trading partner. The trading relationship is increasingly dominated by services.

Since the two countries measure trade differently, their data on the trade gap diverge significantly. According to the UK’s Office for National Statistics, Britain ran a trade surplus of £77.9 billion with the US in 2024. In contrast, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis reported a US surplus of $15.0 billion (approximately £11.8 billion). Regardless, this figure compares favorably to America’s trade deficits with Canada (officially about $63.3 billion) and Mexico (about $166.2 billion), though – once again – there are methodological differences.

Trump has occasionally raised concerns about UK tech and privacy regulations, though not with the same zeal as Vice President Vance. Compared to neighbours like Canada and Mexico – and to a lesser extent, the EU – the UK has caused fewer political headaches for Trump.

The President also harbours a long-standing disdain for the EU, which he once falsely claimed was formed to “screw over the US.” During its negotiations with Trump, the European Commission faced a dual challenge: overcoming Trump’s bias and attempting to unite 27 divergent member states – obstacles the UK, acting alone, did not face.

Sir Keir Rides the Bear: The Personal Side

The Labour government under Keir Starmer did not exactly endear itself to the incoming Trump presidency. Starmer had built a close rapport with Joe Biden – hardly a plus in Trump’s eyes. His dry, lawyerly demeanour is also the polar opposite of Brexit-era Trump favourites like Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage. More seriously, the Labour Party openly supported Vice President Kamala Harris’s 2024 election campaign.

Given this unpromising backdrop, it is remarkable that Starmer has become one of President Trump’s most valued partners.

Personal relationships are often undervalued in high-level diplomacy – except in the case of Donald J. Trump, where they appear to carry outsized weight. The Labour government seems to have recognised this early. Starmer’s former Foreign Secretary, David Lammy, led efforts to build relationships with Trump’s team and to lay the groundwork for leader-level diplomacy.

UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy meets US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken. King Charles Street in 2024 (Photo: Ben Dance / FCDO)

Starmer himself has engaged with Trump very frequently. Since June 2024, he has held at least 16 meetings or phone calls with the President – fewer only than with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy (28) and French President Emmanuel Macron (26), excluding multilateral summits but including the meetings in Washington in August 2025 after the Alaska summit.

The PM has been careful to treat Trump with respect – particularly regarding his peace efforts in Ukraine and the Middle East – while avoiding the groveling deference of NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte. Most notably, Trump was invited for an unprecedented second UK state visit in September 2025. Starmer was likely influenced by Theresa May’s successful hosting of Trump in 2019.

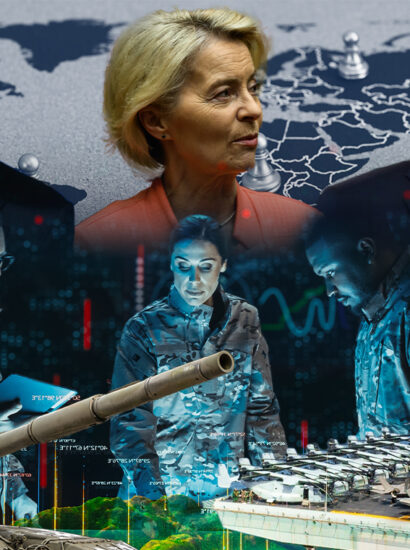

This leads us to Starmer’s personal style. Like Theresa May, he is often described as dry and technocratic. But while May had poor personal chemistry with Trump, Starmer has managed to avoid her pitfalls. It has been speculated that Trump struggles to work with female leaders – especially Angela Merkel, whom he disliked – but this claim is disputed by May herself and seemingly contradicted by Trump’s cordiality with Italian PM Giorgia Meloni and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

More plausibly, Trump did not see May as a political winner, due to her failures in the 2017 election and the Brexit negotiations.

In contrast, Trump likely respects Starmer’s decisive election victory and his success in securing the long-elusive Economic Prosperity Deal with the US. “They’ve been trying to make that deal for 12 years, and he got it done,” Trump said, describing Starmer as a “tough negotiator.”

What’s more, Trump said of their relationship at the G7 meeting in June 2025: “We’ve become friends in a short period of time,” a sentiment he repeated during his meeting with European leaders in August at the White House.

Starmer, for his part, revealed in a recent BBC interview that their bond is rooted in shared family values. Their first conversation came the day after the assassination attempt against Trump, when Starmer inquired about the shooting’s particular effects on Trump’s family. The President later returned the kindness by privately consoling Starmer following the tragic death of his younger brother at Christmas.

An unexpected asset in this relationship may be Victoria Starmer, the Prime Minister’s wife.

For reasons that remain unclear, Trump has spoken of her in glowing – some might say inappropriate – terms: “I don’t know what [Keir Starmer] is doing but she’s very respected, as respected as him. I don’t want to say more, I’ll get myself in trouble. But she’s very, she’s a great woman and is very highly respected.”

Prime Minister Keir Starmer and his wife Victoria at a reception hosted by US President Joe Biden to mark the NATO Summit at the White House (Photo: Simon Dawson / No 10 Downing Street)

Starmer’s choice of ambassador to Washington may have helped, too. While remembered in Europe primarily as a former EU Commissioner, in Britain Lord Mandelson is renowned (or reviled) as one of the architects of New Labour, alongside Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. As the UK’s ambassador to the US, he signed the economic deal with Trump in the Oval Office, and the video footage suggests he can handle Trump with deft diplomacy. However, after his sacking on 11th September due to his past association with Jeffrey Epstein, the PM will have to find a similarly skilled political operator in Washington.

Still, even the best diplomatic choreography cannot entirely offset Trump’s unpredictability – a point made plainly by former Prime Minister Theresa May: “You never quite knew what decisions were going to be taken, even when you were in the room with him. (…) [Going to a press conference] I didn’t know whether or not he was going to say what I thought he was going to say.”

On this front, Starmer’s record is mixed. He did secure notable wins – such as the reduced tariff rates and Trump’s recommitment to NATO (a collective achievement by the Allies) – but has been less successful in substantially shifting Trump’s stance on the Gaza and Ukraine conflicts.

The British Way

There’s no guarantee the warm relationship between Starmer and Trump will last. Nothing is ever certain with the mercurial Donald J. Trump, particularly if the President begins to blame European allies for the failure of peace talks in Ukraine.

Moreover, being close to Trump is not necessarily a political asset within the UK. The President remains deeply unpopular among British voters, above all within Labour’s base. Starmer’s proximity to him may yet prove a liability at home, especially if he cannot deliver on his most important domestic challenges such as the migrant boat crisis or the welfare reforms.

And yet, the Prime Minister has forged a surprisingly effective working relationship with Donald Trump and to Britain’s tangible benefit.

A key factor has been the relatively low number of economic or political grievances Trump holds against the UK, particularly when compared to allies such as Canada or the EU. Another advantage is structural: Starmer leads a post-Brexit Britain, free to negotiate independently and no longer constrained by the 27-member bloc.

Still, structural advantages only go so far – as Theresa May could readily attest. The difference seems to lie, in part, in Starmer. Beyond the UK’s special place in Trump’s mind, the Prime Minister appears to embody qualities that Trump personally values: he is a dealmaker, an election winner, and a man devoted to his family. He has treated Donald J. Trump with respect, engaged with him frequently, and – perhaps most importantly – delivered results.

At the same time, Starmer has succeeded in resetting relations with the European Union. Against expectations, having the cake and eating it too appears to be working.

This, it seems, is the British way.

[…] the United Kingdom, the recent prosecution of former parliamentary researcher Christopher Cash and academic […]