A week ago, Spain’s Defence Minister Margarita Robles was on a military jet that reported GPS interference while flying over the Russian Kaliningrad. In another event on 1 September, the navigation system of a plane carrying Ursula von der Leyen was disrupted due to suspected Russian interference, the European Commission (EC) has said. The EC’s spokesperson said the “GPS jamming happened” while the Commission president was about to arrive in southern Bulgaria, but she still landed safely. In both incidents, the suspect was Russia.

These were just minor but alarming incidents of how Russia is trying to sow disorder and undermine European security. But how did we get here?

Russia’s Unconventional War on Europe

This sabotage campaign represents a clear evolution in Russia’s hybrid war (gibridnaya voyna in Russian) strategy, which includes aggressive and coercive actions with an emphasis on utilizing all tools of the state and associated non-state actors to achieve political power.

According to Russian General Valery Gerasimov, chief of the general staff of the Russian armed forces, the gibridnaya voyna is nothing else than “achieving political goals with minimal military influence by undermining the enemy’s military and economic potential by information and psychological pressure.”

Rather than relying solely on overt cyberattacks or traditional espionage, the GRU deployed low-tech but high-impact disruptive tactics, focusing on plausible deniability.

This approach is consistent with the GRU’s operational profile post-2018, which includes poisoning attacks, undersea infrastructure disruptions, and influence campaigns in both Europe and Africa. The use of migrant populations, petty criminals, and Telegram channels provides an expendable and decentralized force—one difficult for security services to preempt or disrupt.

Operational work is led by Russia’s military intelligence, GRU Units 29155 and 54654. The whole scheme was coordinated by the Service for Special Activities (SSA).

Andrei Averyanov, the GRU’s deputy head, established the SSA and was the key figure in planning and coordinating these secret operations. Unit 29155 is responsible for an array of infamous operations, including the Salisbury poisonings and the attempted assassination of Alexei Navalny.

However, Russia is increasingly using criminal proxies, rather than regular intelligence officers (who were expelled en masse from European embassies in 2022), to carry out attacks. In July, for example, three men were convicted of setting fire to a Ukraine-linked warehouse in London on behalf of the Wagner group, a Russian mercenary outfit. This allows them greater flexibility and deniability. Its use may explain the recent surge in low-tech attacks.

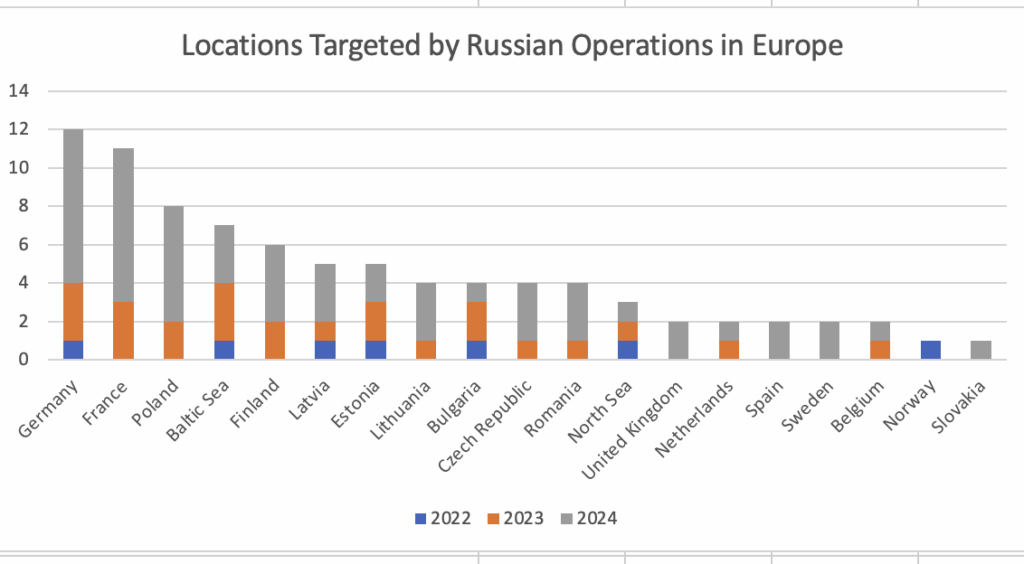

The number of suspected Russian sabotage operations in Europe almost quadrupled between 2023 and 2024, with more than 30 incidents recorded in 2024. These included damage to the Baltic Sea’s undersea cables, as well as interference with water supply systems in Finland and Germany, and attacks on military equipment, civilian buildings across northern and eastern Europe.

Another common Russian tactic has been influence operations that target European politicians to erode political support for Ukraine, both at the European Union and national levels.

A key example is the Voice of Europe scandal, which centered on a radical news site that became a tool for the Kremlin to platform Russia-friendly content and funnel money to pro-Russian politicians in various European countries.

Alongside these more sophisticated measures, there have been numerous acts of vandalism seemingly designed to sow confusion and disrupt daily life.

It also includes the thousands of bomb threats in schools in Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, which led to several days of closures in 2024.

The bulk of the targets, according to an IISS report, are in Ukraine or are connected to European efforts to support or supply Ukraine with military and other civilian hardware. The uptick of incidents coincided with Russia’s all-out invasion of Ukraine, launched in February 2022. The spike in the incidents was in 2023-24 and has declined in the first half of 2025.

Attacks Against the Baltic Sea Optic Cables

Russian sabotage efforts, particularly against critical infrastructure, are not a recent development. The Kremlin has historically targeted submarine cables. In October 2015, United States authorities monitored Russian submarine patrols and the Russian surface ship ‘Yantar’ in a corridor of the North Atlantic that hosts a cluster of undersea cables. Some of the most disruptive attacks have involved anchor-dragging by Russia’s “shadow fleet”.

On 7 October 2023, a vessel registered in China cut two telecommunications cables in the Baltic Sea connecting Estonia to Finland and Sweden. It broke a natural gas pipeline linking Finland and Estonia.

Recent Russian sabotage incidents in the Baltic Sea include those involving the Cook Islands-flagged Eagle S, which dragged its anchor and cut the Estlink-2 undersea cable in the Gulf of Finland, and the Chinese-flagged Yi Peng 3, which is suspected of having deliberately dragged its anchor to cut the C-Lion1 cable connecting Finland and Germany and the Arelion cable linking Sweden and Lithuania.

Four similar incidents occurred in late 2024 and early 2025, three near Sweden’s strategic Gotland island, and affected telecoms, power, and gas lines connecting Nordic countries, the Baltic states, and Germany. None of the ongoing investigations have so far proved ill intent, although some of the cargo ships suspected of sabotage are part of Russia’s so-called shadow fleet.

The tactic is very simple: state organs enlist a third party that would typically operate in the target maritime space, for example, a captain of a commercial vessel. The third party then drops anchor near the target and proceeds to drag it along the seabed until the cable is severely damaged or cut outright. This tactic is particularly well-suited to the Baltic Sea due to its shallow waters and critical undersea cable infrastructure.

It doesn’t require a significant financial investment. On the other hand, it is very easy to deny any connection to it, as the operations do not directly involve any state instrument; furthermore, accidental anchor-related damages happen very often.

The third benefit is the damage that these operations can cause—repairing just one severed cable or pipeline costs between €5 million and €150 million, not including the economic damage inflicted by the loss of capacity or the additional costs of policing, investigating, and defending the maritime domain.

Incidents targeting Europe’s infrastructure do not appear to be meant to cause significant disruption but rather point to its vulnerability to outside interference. The persistence of such incidents and their concentration in the highly contested Baltic Sea area leave room for concerns about a deliberate campaign.

Answering to this challenge, in January 2025, NATO announced the ‘Baltic Sentry’ initiative, which will deploy frigates, patrol aircraft, and maritime drones to monitor critical infrastructure in the area. Notably, the deployment will have the power to board, impound, and arrest crews suspected of sabotage.

Locations Targeted by Russian Operations in Europe

Own edit, data source: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/TQ0FMQ

European Arson and Espionage Campaign—Punishment for Supporting Ukraine

Europe’s critical infrastructure is particularly vulnerable to sabotage because it is in such a poor state following decades of deferred maintenance and a lack of investment from national governments and the private sector.

As IISS data shows, the sharp escalation of sabotage happened after the Western removal of restrictions on Ukraine’s use of advanced Western-supplied weapons, particularly long-range systems used to strike inside Russia in 2024.

During the year, Russia’s steamroller offensive secured only incremental gains in Ukraine but incurred staggering losses of personnel. Meanwhile, Ukrainian drones wreaked havoc on Russia’s oil installations, reaching targets as far afield as the Ural mountains. These developments may have prompted Russia to ramp up deniable attacks on Europe’s defense industry, which was only occasionally targeted in the previous decade.

ACLED data show that more than half of all suspicious events since February 2022 occurred in 2024. Around 35 percent of these events were sabotage, and another 27 percent were unauthorized drone overflights.

In February, the US and Germany called out a Russian plot to assassinate the head of Rheinmetall, Armin Papperger, an arms producer involved in supplying the Ukrainian army and opening assembly sites in Ukraine. In May, a fire at another weapons producer – a Diehl factory near Berlin – destroyed four floors and caused partial collapse of the building. German authorities, citing communications intercepts, attributed the incident to Russian sabotage.

Civilian or probable dual-use targets also faced an increased threat of sabotage, with attacks becoming more reckless.

Between March and May 2024, suspected Belarusian and Ukrainian recruits of Russian agents set ablaze three warehouses in Lithuania, Spain, and the UK, as well as a shopping mall in Poland. In July, three explosions involving flammable parcels occurred at warehouses in Germany, Poland, and the UK, with a fourth attempt foiled.

The incidents prompted alleged US backchanneling with Russia, according to The New York Times, to dissuade further attempts to send flammable parcels across the Atlantic due to the risk of mid-air explosions.

Furthermore, military sites became increasingly targeted. At the end of May, a cache of explosives was discovered at a pipeline hub supplying military bases in Germany’s Bellheim municipality.

In August, security breaches occurred at two military bases in Germany’s Nordrhein-Westfalen, prompting concerns about water contamination at and around them. In addition, between August 2024 and February 2025, ACLED records about 20 sightings of unidentified drones hovering over military bases or warships in or near Germany and the UK.

Similar incidents occurred on at least two occasions near Romania’s Mihail Kogalniceanu airbase in April 2024. And other facilities in Germany, Poland, and Romania are extensively used for supplying, training, and coordinating the Ukrainian armed force.

Full list of notable incidents on the European mainland:

- Poland Spying November, 2023

- Estonia Vandalism December, 2023

- Poland Paint Factory Arson (aborted) January, 2024

- Warsaw Hardware Store Arson April, 2024

- Vilnius IKEA Arson May, 2024

- Warsaw Marwilska Shopping Center Arson May, 2024

- DHL Package Explosions (various locations) May, 2024

- Second Package Plot (Germany) July, 2024

- Drone Incidents and Cyberattacks at European Airports September, 2025

What’s Next?

In comparison to the peak observed in late 2024 and early 2025, when the standoff between Russia and Ukraine’s supporters was most pronounced, incidents across Europe in which Russian involvement is suspected appeared to diminish by March 2025. Despite the increasing suspicion of Russian activity, NATO allies have exercised caution in refraining from overreacting to covert operations.In addition to the actions taken in the Baltic Sea, the targets of suspected Russian activity respond in any way they can.

The Russian consulate in Poznan was closed by Polish authorities in late 2024 due to its involvement in coordinating sabotage attempts in the country. In May 2025, the consulate in Krakow was closed in response to the Warsaw retail mall fire. As a result of the influx of asylum applicants from impoverished nations, Finland has maintained its land crossings with Russia closed for more than a year.

Efforts to deter by denial have bolstered resilience. Submarine surveillance, the establishment of NATO’s Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cell, and public-private partnerships to fortify physical and cyber infrastructure have increased the cost of sabotage. Still, numerous NATO nations are unable to replicate these partnerships independently. Russia has not been deterred by resilience alone, particularly in light of the fact that sabotage operations are still cost-effective and prevalent in the labor economy.