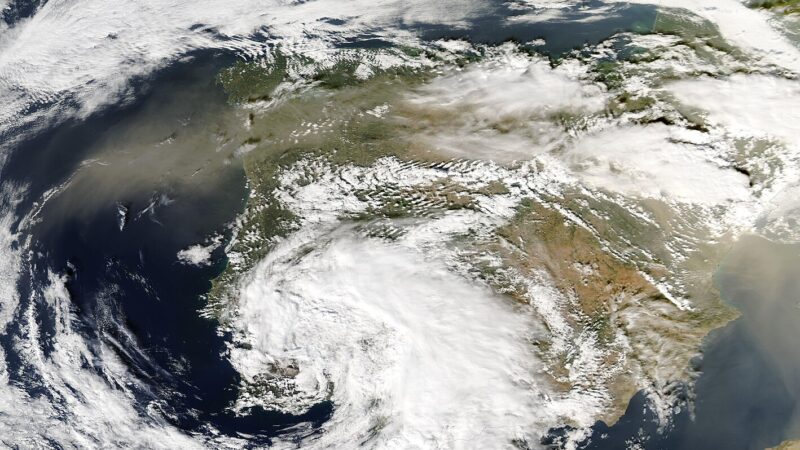

The climate report published by the European Commission in November publicized the most significant yearly decline in EU greenhouse gas emissions in decades, while at the end of October in Valencia, more than 200 people suffered lethal consequences of the DANA flood—a flood which is a direct result of climate change.

The undeniable success of EU climate regulations clashes starkly with the devastation seen across member states in 2024; think of the forest fires already seen in March in Greece or of Germany’s severe flooding from storms Orinoco (June 2024) and Boris (September 2024). Yet, there are still people who dismiss the importance of climate change, such as American President-elect Donald J. Trump and his new energy secretary candidate Chris Wright, who, whilst acknowledging the link between burning fossil fuels and climate change also expressed doubt that climate change is interconnected to worsening extreme weather.

Alas, there is a reason why we arrived at such extremes in climate discourse.

Climate reporting often swings between the poles of triumph and catastrophe.

On one hand, the EU’s progress—an 8.3 percent drop in greenhouse gas emissions from last year—represents a significant success of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), the EU Effort Sharing Regulation and the EU Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry Regulation, yet, on the other, media narratives emphasize severe events like the DANA flood, portraying a world on the brink of collapse.

Thus, inconsistency arises when these narratives lack balance.

Such imbalance is the direct result of how the media frames climate issues. Reporting on climate regulations, agreements, or emissions reductions is often technical and, for the audience, hard to understand. These reports, while paramount, get beclouded by dramatic and moving coverages of disasters; catastrophes draw immediate public attention due to their vivid, urgent and easily relatable nature, features all uncharacteristic of climate policy and decision-making. Thus, such phenomena makes for lopsided narratives.

Dr. Kristen Swain, Associate Professor of Integrated Marketing Communication at Ole Miss argued in 2012 that media framings influence how audiences interpret the climate issue, assign blame and envision systematic solutions. Such classic, episodic media coverage of disasters, of DANA or of the March forest fires in Greece, makes climate change feel immediate but generally fails to provide actionable solutions.

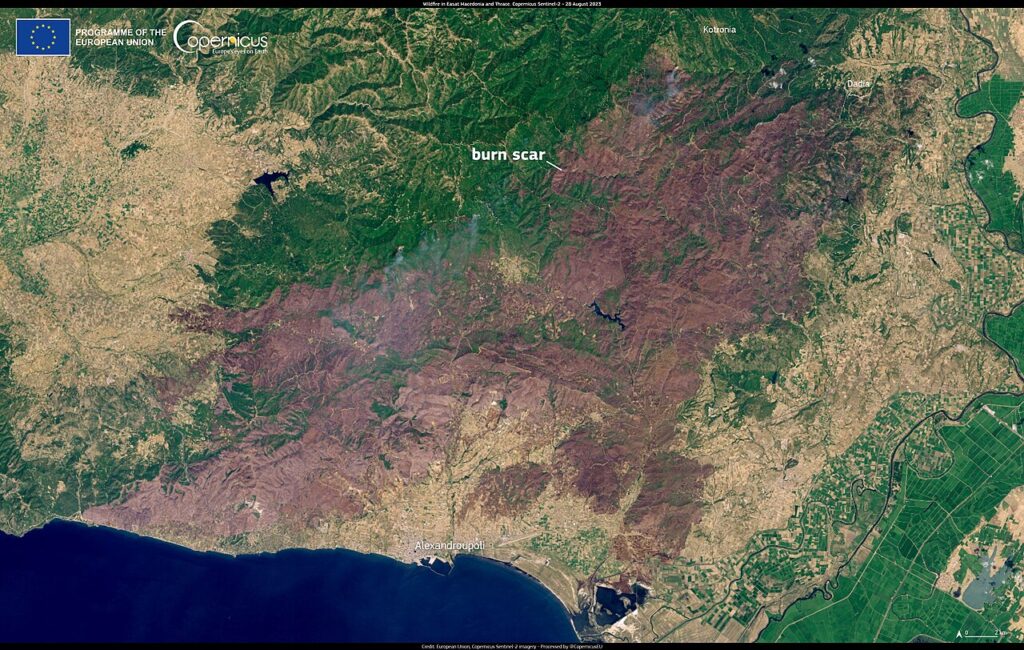

On 28 August, one of the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites captured this image of the entire affected area where the burnt scar is visible (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Focusing on these catastrophic consequences can mobilize concern but risks leave audiences disengaged.

Alternative framings, like economic opportunity measures, health benefits or even national security implications could resonate with diverse audiences but remain underutilized.

The prevalence of extreme narratives is rooted in both strategic and practical considerations. First, public understanding of climate change is often shallow – as Swain put it, many people fail to distinguish between weather and climate. Thus, oversimplification in media coverage becomes a necessity. Secondly, for policymakers like the European Commission, building upon successes such as emissions reductions is the way to validate their strategies – this is particularly the case with unpopular regulations like the ETS.

Conversely, environmental organizations spotlight disasters to emphasize the urgency for far more aggressive measures, but these framings lack day-to-day relevance, leaving individuals struggling to translate awareness into meaningful behavioralchanges.

As media coverage tends to neglect adaptation strategies or solutions in favor of alarming headlines, an imbalance is emerging, which is compounded by political and ideological influences: conservative skepticism is inclined to diminish the perceived urgency of climate change while progressive narratives can unintentionally foster despair by overemphasizing catastrophe.

Thus, what’s missing in the climate conversation is a framework that reconciles such extremes. The European Commission’s climate report and the realities of climate disasters are not contradictory, but are two sides of the same coin. Public understanding of climate change still suffers from a lack of context as few recognize that mitigation efforts can coexist with worsening disasters due to the lagging impacts of past emissions.

[…] collapse of the German government coalition and Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez due to the flood disaster in Valencia, although by the informal EU summit a day later they had both joined their colleagues […]