China’s grand strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative is adapting to the new reality. Many details from the October summit indicate that Beijing is increasingly politicizing economic cooperation, in order to respond to the changing challenges coming from the international environment. Alongside China, Russia is a key player: even though both Asian major powers take risks in deepening their relationship, they have no other choice due to military cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

Against the backdrop of the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the recent tensions in Gaza, China and its allies marked the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). For a week in October, Beijing experienced a renewed energy, which had been missing in the Chinese capital since the outbreak of the pandemic. As the city turned into a diplomatic hub, it witnessed a heightened police presence and a constant stream of large black convoys traversing its streets day and night.

While this may seem taxing, the people of Beijing take pride in being a significant player in global politics.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) played a pivotal role in establishing China as a superpower. Premier Xi Jinping unveiled this vision on September 7, 2013, during a lecture at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan. In his speech, Xi presented his foreign policy agenda, centered around the “new Silk Road.” This initiative drew inspiration from the historical Silk Road, with the goal of creating a trade corridor linking Europe and East Asia. The core idea behind this plan was straightforward: fostering cross-border infrastructure to enhance people-to-people connectivity, ultimately contributing, under certain conditions, to global peace and prosperity.

The Big Comeback

The 10th-anniversary celebration of the Chinese grand strategy had to be grand in scale. However, assessing its success remains challenging. According to Chinese media, the third Belt and Road Forum was deemed a “complete success,” resulting in nearly 460 achievements and drawing over 10 000 participants from more than 150 countries and 40 international organizations. Conversely, Western news outlets pointed out that overall interest from world leaders was relatively low. According to The Diplomat magazine, only 23 heads of state or government attended, a decrease from the 30 leaders in 2017 and 37 in 2019.

The decline in the number of European leaders attending was particularly noticeable. This year, only Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic were in attendance. In contrast, during both the 2017 and 2019 summits, leaders from Belarus, Czechia, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland also participated.

Surprisingly, there was a low representation of African leaders, despite being a priority focus for BRI funds. Only Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, and the Republic of Congo were present, a relatively small number considering Beijing’s ambitions in the region. Similarly, the absence of Southeast Asian leaders was puzzling. As highlighted by The Diplomat, all 11 regional states, including the 10 ASEAN members and Timor-Leste, have signed agreements related to Belt and Road cooperation. During the first Belt and Road Forum (BRF), seven Southeast Asian leaders attended, followed by nine during the second BRF, with Indonesia sending its vice president. However, this year, only half of the ASEAN member states sent their heads of state or government to the event, namely Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The decreasing trend of the attendees number have both political and technical reasons. There are several explanations for the decreasing number of invitees. Firstly, the international climate has changed significantly since 2019. Tensions between the United States and China have escalated, leading to the emergence of a more polarized world order.

President Joe Biden greets and poses for a photo with Chinese President Xi Jingping ahead of their bilateral meeting, Monday, November 14, 2022, at the Mulia Resort in Bali, Indonesia (Photo by Adam Schultz / White House / Flickr.com / RawPixel)

Many countries are not in a position to send positive signals to China, as doing so could provoke a response from the United States.

On the other hand, technical reasons have also surfaced, drawing attention to the shortcomings in Chinese foreign policy. China officially abandoned its zero-Covid policy at the beginning of this year and subsequently launched a visible diplomatic offensive. Xi Jinping participated in numerous important bilateral and multilateral meetings, including with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, French President Emmanuel Macron, and Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission.

It’s essential to mention the BRICS summit in South Africa and the ASEAN summit. During these events, Xi Jinping conducted most of his crucial meetings, leaving many world leaders with little to discuss with China by the time the BRI summit was scheduled at the year’s end.

The Vision: Highways. The Reality: Walls

Contrary to the focus of the media, it was not so much the guest list but rather the official speeches and analyses related to the event that made the forum interesting. In his opening speech, Xi Jinping assessed the future of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in eight key points. The central theme here is the “high-quality Belt and Road cooperation.” These specific measures highlight key areas such as the digital economy, technological innovation, eco-friendly development, and enhancing the quality of life – all of which are central to the global efforts of various countries. These aspects are tightly interwoven with future development.

According to reports from Chinese state media, the Belt and Road Forum (BRF), with its new approach, delivered a total of 458 outcomes, significantly surpassing the number achieved during the second BRF in 2019. The Global Times article emphasized that these outcomes encompassed initiatives focused on deepening connectivity, fostering eco-friendly development, and enhancing cooperation in the digital economy. Additionally, the CEO Conference held during this forum resulted in business deals worth $97.2 billion.

Despite the impressive statistics provided by Chinese state media, no joint declaration was signed by the participating parties at the conclusion of the meeting. While Western media suggested this could be attributed to partner countries’ skepticism, the actual reasons behind this absence may be more intricate.

First and foremost, China began to slow down the outflow of operational capital and loans to foreign countries as early as 2017. This marked a noticeable change from its previous, high-paced lending and investment policies that gained momentum with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Many developing countries faced challenges in repaying Chinese loans, and external factors, especially escalating conflicts with the United States, prompted China to scale back its previous spendthrift financial policies.

During the third symposium of the BRI held in 2021, Xi Jinping indicated that China now prefers “small but beautiful” investments over grand and extravagant projects.

Since then, this process has intensified, causing conflicts between China and its partners. In the current international climate, China’s interest lies not in offering long-term, expensive, and high-risk loans.

Therefore, instead of focusing on infrastructure, so-called hard connectivity investments, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is shifting its focus toward soft connectivity.

This primarily involves gaining market share for high-tech products and supporting areas compatible with digitization. The BRI has fundamentally transformed: it is evolving into a cooperation aimed at the dissemination of tools and services facilitating digital transition and the internationalization of the RMB, rather than a project for connecting the infrastructure of the Eurasian supercontinent.

This process leads to the politicization of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The evolving nature of this cooperation indicates a more overt role in the ongoing Cold War with the United States. The conflict between the two superpowers is intensifying in the economic dimension, with a particular emphasis on technology. In Washington and other Western capitals, there is a growing perception of China as a significant competitor in Chinese products, with their displacement, especially from markets in developing countries, being of paramount importance.

A well-known example is Huawei, which, with its advanced 5G and 6G technologies, can pose a serious challenge to Western companies in building digital infrastructure. However, the United States has imposed sanctions on numerous Chinese companies. In response, China is limiting the export of raw materials necessary for the production of high-tech products.

Cell tower (Photo: RawPixel)

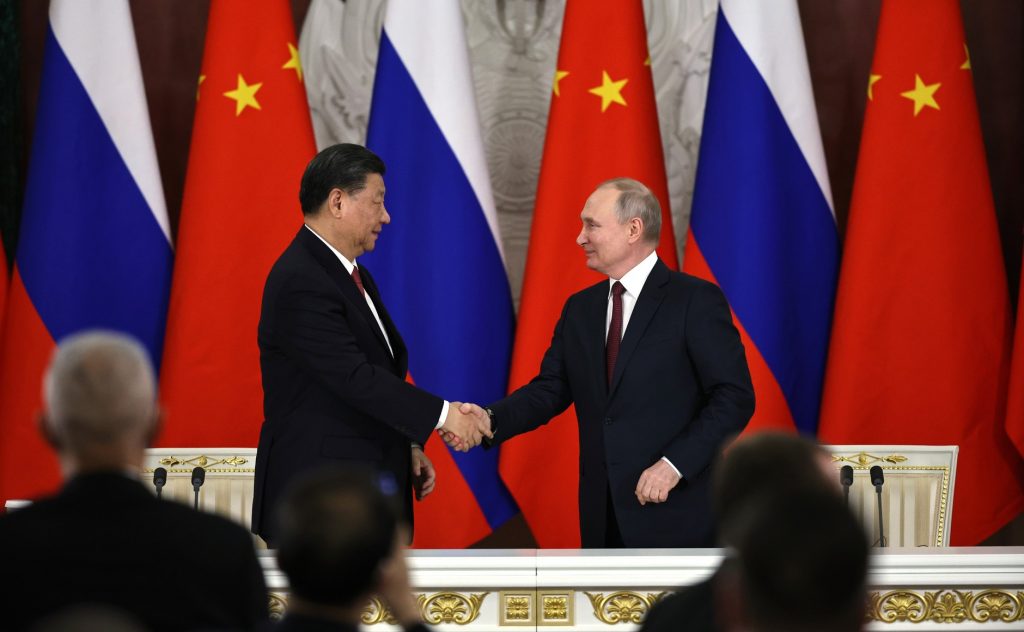

Putin, the Grey Elephant

Although several interesting developments occurred at the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) summit, Vladimir Putin stole the spotlight. In the increasingly tense international situation, analysts are predicting a higher likelihood of armed conflict, and the danger of this is further exacerbated by the visible rapprochement between China and Russia. For Putin, the forum provided an opportunity to meet other leaders without fear of arrest, given his indictment by the International Criminal Court for war crimes which had kept him away from September’s Brics summit in South Africa.

But the invitation came with a price: Putin had to declare Russia’s junior role in the partnership with China. In his speech, Putin characterized the Russia-led Greater Eurasian Partnership (GEP), an idea Moscow has advanced as a counterpoint to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as a regional or “regional” endeavor. Simultaneously, he enthusiastically labeled the BRI as a “global” undertaking.

Putin’s invitation also suggests that Beijing has let go of its Western connections and is anticipating the breakdown of the international system.

Despite multiple warnings from prominent EU figures over the past weeks, including a recent visit to Beijing by the EU’s chief diplomat Josep Borrell, highlighting that China’s refusal to condemn the Ukraine invasion is negatively affecting its reputation in Europe, the two leaders are holding their meeting.

For Russia, building relationships results in a loss of prestige, while China pays a price in terms of its Western connections. However, the economic cooperation partially compensates both parties for these losses.

Putin underscored the substantial bilateral trade volume between Russia and China, which has not only met but exceeded the previously set target, reaching nearly US$200 billion. A significant portion of this total comprises Russian energy and weapons exports to China. The potential for a substantial increase in gas exports exists, particularly if the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline is constructed. This pipeline would transport gas from Russia’s Yamal gas fields, which previously supplied Europe, through Mongolia to China. Analysts have noted that the project was conspicuously absent from discussions during the summit, potentially raising concerns on the Russian side.

Vladimir Putin welcomes Xi in Moscow during Xi’s visit to Russia in March 2023 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Kremlin.ru)

While there may be obstacles to further growth in economic relationships, the prospects of military cooperation override any concerns. The United States is increasingly mobilizing resources in the Indo-Pacific region, and multilateral partnerships like the Quad and AUKUS are pressuring both China and Russia. These two Asian countries are steadily expanding their military cooperation. In late August, Russian naval vessels, alongside Chinese ships, concluded an extensive 13 000-kilometer patrol in the Pacific, involving the largest warships from the Russian Pacific Fleet in a collaborative naval exercise with the PLA. Together, these warships undertook a journey that encompassed the Sea of Japan, the Sea of Okhotsk, the Bering Sea, and the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

Concurrently, as per the official statement from the Russian Ministry of Defence, the Pacific Fleet’s corvette Gremyashy conducted simulated exercises in searching for enemy submarines in the northern part of the Sea of Japan at the close of August.

According to reports, military and naval cooperation is deepening, and some analyses suggest that China’s latest Type 096 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) possesses advanced stealth and offensive capabilities, posing an increased threat to American forces. Reuters recently reported that the submarine is being developed with Russian technology.

In an article published in August 2021 by Matthew Funaiole and fellow authors at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank, it was noted that in order to reach Hawaii and the northwestern United States, the older Type 094 submarines have to navigate through crucial chokepoints, such as the Miyako Strait and Bashi Channel within the First Island Chain, which encompasses Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines.

Funaiole and the other authors mentioned that the JL-2 missile’s limited range and reported acoustic signature could potentially make it vulnerable to detection by US and allied anti-submarine forces.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the development of Chinese submarine capabilities, and the deepening military cooperation with Russia all point to the duality in China’s foreign policy strategy.

While in the Eurasian continent and Africa, China is primarily engaged in economic dimensions to counter American pressure, the Indo-Pacific region is becoming increasingly focused on military confrontation.

[…] most likely winners of the coming year are the members of the expanded BRICS bloc, with China leading the way. The empowered BRICS+ can be the rival of the G7 countries, in every aspect. The […]

[…] President Xi Jinping unveiled the Maritime Silk Road plan in Jakarta, later continuing as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This not-so-coincidental convergence shows how the fates of the two Asian countries are closely […]