Several people have died in protests across Venezuela as demonstrators demanded that President Nicolás Maduro acknowledge defeat in the July 28 election. Since then, more than 2 000 people have been arrested, 21 killed, and dozens more have been severely injured in the repression wave of the regime. Amid growing unrest in the country, Nicolás Maduro ordered the government-controlled Supreme Court to audit his contested presidential election victory.

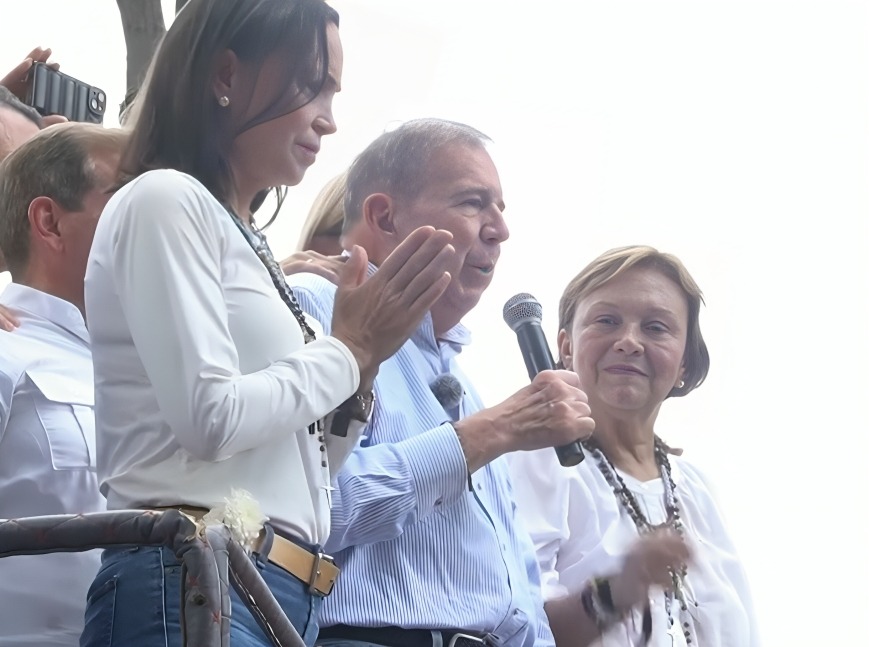

Following the protests, opposition leader Maria Corina Machado went hiding after being threatened with arrest. To quell large-scale protests in support of retired diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia, President Nicolás Maduro intensified his repression against the opposition. In the meantime, the international community demanded that “all the tally sheets be released promptly” to ensure complete transparency of the election on July 28.

End of the Chavismo?

It will take pressure from the outside and inside to force the ruling coalition to give up power. The majority of countries in the world have already made it clear that they will not overlook the issue. “The international community has a great responsibility,” Machado told Americas Quarterly. Venezuela’s opposition leader said it would prove their candidates had won almost 70 percent of the ballots. Nevertheless, Chavismo – the current government’s ideology named after Hugo Chavez – seems weaker than ever: 75 percent of Venezuelans want a change in leadership. Even in the poorest barrios, former Chavista strongholds, support for Maduro has eroded.

-

Hugo Chávez in 2010 (Photo: Presidencia de la Nación Argentina / Wikimedia Commons)

US President Joe Biden and Brazil President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva have also called for the release of vote tallies. About 20 nations have pushed Maduro to present a complete and verifiable vote tabulation to no avail. At the same time, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken recognized that González won the most votes in the contest.

It was also rumored that the Biden administration offered Nicolás Maduro and his aides an amnesty to leave power in Venezuela. “We have not made any offers of amnesty to Maduro or others since the election,” a senior US official, who spoke under condition of anonymity, said. “We are considering a range of options to incentivize and pressure Maduro to recognize the election results and will continue to do so.”

International Pressure on Maduro

EU members, particularly France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, have urged transparency. However, unlike the US and a few other nations, the EU has not acknowledged González Urrutia’s win as the opposition leader.

Even Maduro’s leftist allies, Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia demanded the release of the voting records. The foreign ministers of these three nations traveled to the capital of Venezuela to negotiate a peaceful resolution of the situation.

Gabriel Boric, the President of Chile, on the other hand, stated that the Maduro regime attempted to “commit fraud.” The vehemence with which the Chilean President has accused Maduro is supported by leaders of his generation and political persuasion but is causing a hive of anger in Caracas. Venezuelan Foreign Minister Yvan Gil called Boric a “pinochetista” who wants a coup d’état.

The Argentine Foreign Ministry issued a communiqué on the 7th of August, in which they pointed out the opposition candidate, Edmundo González, as the “undisputed winner,” which ended with the withdrawal of the Argentine diplomatic staff from Caracas. The Argentine President, Javier Milei, has also joined the list of presidents and former presidents who have condemned the judicial encirclement of González and María Corina Machado.

-

María Corina Machado with Edmundo González addressing the nation in Caracas (Photo: Voz de América / Wikimedia Commons)

Meanwhile, the Organization of American States (OAS) failed to pass a resolution requiring the electoral authorities to publish detailed election results. On August 7, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) rejected the proposal of the President of Panama, José Raúl Mulino, to hold a regional summit of presidents to address the crisis in Venezuela. ALBA is made up of the five Caribbean island states: Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Bolivia.

Lula’s Game

Celso Amorim, a former Brazilian prime minister and special advisor to Lula, has said he fears a civil war in Venezuela and called for another vote, with EU observers, to settle the crisis. Lula himself is looking for a dialogical way out of the open crisis in Venezuela.

Brazilian Foreign Ministry is leading the mediation efforts with Colombia and Mexico to solve the crisis. This initiative was supported by the United States, France, Spain, and Latin American countries. The Biden administration, which is too busy with other international crises (the Middle East, Ukraine, and the Pacific), happily let the leftist trio of Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico handle the situation.

“Rather than taking the lead in pushing for Maduro to step down and threatening sanctions and other reprisals if he refuses as the White House has in the past, the current administration has placed its hopes in the triad of leftist Latin American governments to persuade him to yield,” Kren DeYoung and Samantha Schmidt wrote in The Washington Post.

After Venezuela’s last election, in 2018, Maduro was proclaimed winner amid widespread accusations of fraud. The United States and many other countries recognized the then-speaker of parliament, Juan Guaidó, as acting President, but it did little to change the situation. Eventually, Maduro kept power, and the historical resentment of US power in its backyard grew.

-

Nicolás Maduro’s inauguration as President in 2019 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

If the Brazilian-led talks work, it will be a victory for Lula’s “third way” diplomatic strategy. The strategy “which seeks to further the economic concerns of developing countries without picking a side in the great powers conflict in the current global Cold War 2.0.”

The Growing Shino-Russian Influence in Latin America

Russia and China, two of Caracas’s most important international allies and a major trading partner, are leading some analysts to believe Maduro might be able to hold onto power in the end. Even as public support for the Kremlin’s foreign interventions declines in Russia, Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping are forced to back Nicolas Maduro, the collapsing strongman of Venezuela, because of these debts and other economic ties.

Russia and China operate to gain influence in many different ways. However, the main way they exert influence is by using both overt and covert tactics to weaken US leadership in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) area. Russia uses influence to ensure that these countries prefer Russian weapons, openly support its war in Ukraine, remain silent in international fora, and remain reluctant to join the Western sanctions campaign. Due to its inability to establish an economic connection with LAC on the same scale as China, Russia has limited its involvement to bilateral agreements, military-to-military relations, and security cooperation. Putin frequently enjoys socializing with the most despotic regimes in the area.

Taiwan has eight of its global allies in this region. Thus, China’s primary goal is to lower Taipei’s support. Beijing has worked closely with Venezuela and, for a while, with Ecuador and Bolivia in an effort to shield its own autocratic political model from criticism.

Billions of Dollars in Investments

Like Maduro’s regime, which is the leading purchaser of Russian military equipment, which is vital for President Vladimir Putin, especially as US and EU sanctions aim to devastate the Russian defense industry. Over the years, Venezuela has purchased nearly $10 billion in Russian weapons, including sophisticated S-300 anti-aircraft missiles. Russia aims to leverage the region to push back against US action in Europe, where it considers itself entitled to a privileged “sphere of influence.”

Like Russia, China got into bed with the Venezuelan regime during the 2000s. Shortly after Xin Jinping came to power, Beijing upgraded the bilateral relationship between the two countries to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.

In 2019, when the then-president of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, declared himself interim President, Beijing continued to recognize Maduro, using its veto power in the UN Security Council to block a resolution recognizing Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimate President.

Venezuela’s dependence on China became increasingly evident. China became the Venezuelan government’s key lender as it sought monetary liquidity to keep the Chavista social program alive. The loans are committed to future oil production. The flow was enormous: $62 billion. China maintained its support when a US oil embargo was in force, which helped Caracas place its oil in the Chinese market.

Russia engages with Maduro’s regime through its well-known state-owned companies and other entities, including Rosoboronexport (military products), Rosatom (nuclear technologies), Rosneft (petroleum refining), and Rusal (aluminum industry).

Through their affiliation with the state oil monopoly Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), Rosneft has channeled billions of USD in loans to the Chavez/Maduro governments during the last decade. Meanwhile, the company handled a total of three million tons of oil in 2017 with their operations in Venezuela; in general, Russia has invested in many Venezuelan industries, from banks to bus assembly plants.

In monetary terms, Maduro’s fall could mean even greater losses for China, whose investments in Venezuela are estimated at around 60 billion dollars, at least three times those of Russia.

While China obtained a very needed source of oil for its rapidly growing economy, Chavez was able to reduce Venezuela’s dependence on the United States as their principal export market. Meanwhile, the Chinese tech giants have helped Maduro’s regime in their efforts at internal spying, and (like Russia) China has sold expensive arms to Venezuela.

Is there a way out for Maduro and his regime?

Maduro is willing to take the next step—and become a fully rogue, isolated, Nicaragua—style regime if necessary to retain power. But what will happen if he must step down?

Instead of immediately admitting defeat, Maduro and his inner circle may use recognition of election results as a negotiation tool, like when Daniel Ortega of the Sandinista National Liberation Front handed over power in 1990. Alternatively, a fracture within the ruling coalition could lead to an annulment of the vote count, as seen when Bolivia’s Congress annulled elections in 2019 due to allegations of fraud, but this is the most improbable scenario.

A military coup is just as unlikely to happen for several reasons: the generals and the others in the military’s top brass have much to lose, and in a potential regime change, many must give up lucrative state corruption schemes and face criminal charges.

Although complex, pathways to a democratic transition still exist.

From here, possible scenarios include the government violently and successfully stifling dissent, as happened after other elections celebrated in the past decade, the release of a new election tally with verifiable evidence, or a negotiated solution between the government and the opposition.

Maduro’s Chavismo party has long counted on its popular electoral strength for an air of legitimacy, but it has gradually lost support. In the late 1980s, a popular uprising led to Chávez’s elevation as the country’s leader — and Maduro’s own narrative regularly refers back to those events to give his government a direct link to that history to fall back on for legitimacy.