The beginning of Ukraine’s 2023 summer and spring counter-offensive came as no surprise to anyone. It had been heavily discussed internationally and domestically, even before Russia and Wagner managed to conquer Bakhmut in May. However, exactly how the Ukrainian attack is going is heavily contested. On one hand there is the narrative that it has been a crushing failure, even with the Western equipment. On the other side, there is the assertion that everything is going according to plan. The latter seems difficult to believe given the reporting of extremely difficult fights and slow gains taking place.

Russia Dug in Deep

During the time that Ukraine focused on absorbing Russian offensives over the winter and spring, Kyiv continued to state the intention to take back the military initiative. New units were being generated, in some case using new equipment, specifically to help a new offensive. For their part, Russia invested time and resources in preparing deep fixed defences.

There are some common general features of defensive positioning: extensive minefields, the use of anti-tank obstacles and ditches, and a well-developed trench system. The focus of Russian defensive construction was in the south of Ukraine, with the priority of protecting the land bridge to Crimea.

Defensive schemes according to the Russian and Soviet doctrine first have a security zone several kilometres in depth. Any attacker pushing into that security zone would suffer attrition from defenders, minefields and indirect fire. With many of the guns and MLRS system (Multiple Launch Rocket System) delivering those fires safely positioned behind the primary defence zone.

Defence formations from left to right: anti-tank ditch, dragon’s teeth, fortified trench system (Source: István Resperger / ATV)

The precise objectives of the offensive path in order to attack these defences is ultimately known only to Ukrainian high command. Analysts and observers hypothesised a number of potential options. South to cut the land bridge to the Russian positions in Kherson and Crimea or perhaps east into Donetsk or Luhansk. Or if some Russian media commentators are to be believed, some outside chances like a Ukrainian offensive to Belgorod, towards Moscow or an invasion of Belarus.

Some had expected this operation to be launched by Ukraine in the spring. Instead the period up to the first week of June was dominated by different kinds of shaping operations. A number of these were purely informational or political, with different actors either trying to build up expectations or tamp down the same expectations for Ukraine’s eventual offensive. While this would have very little impact on how the military side of the offensive would play out, it would help shape public perceptions.

The months of May and June also saw cross-border incursions from Ukraine into the Belgorod region of Russia. Up to this point it had been rare for forces to cross from Ukraine into this Russian territory. Nevertheless, we could follow relatively small-scale raids by small formations of volunteer Russian formations. Small forces with small amounts of heavy equipment, one or two tanks and a small collection of armoured vehicles were able to cross the border successfully. Some western vehicles were later captured and towed to the rear by Russian forces.

Photograph of a Ukrainian convoy of Russian Volunteer Corps vehicles (identified by the armband) during the Shebekin offensive in Belgorod, Russia. Taken on June 1, 2023 on the outskirts of Shebekino in Belgorod Oblast (Russia) by a soldier of the Polish Volunteer Corps (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In the second raid in June it took weeks for Russian forces to finally throw these volunteer units back across the border. The military damage done may have been relatively minor, but it proved how weak Russian border defences had become. Another Ukrainian objective could have been to prompt Russian forces to concentrate more units along the border rather than in those areas where Ukraine’s main forces would eventually strike.

Bakhmut: Unimportantly Important

Wagner troops had been steadily withdrawn from the region and replaced by Russian regulars. It seems that Ukrainian forces took the opportunity by pushing back on the flanks of the city, reversing some Russian gains during their respective offensive. One potential objective of the Ukrainian forces is the intention to draw in additional Russian troops to defend Bakhmut.

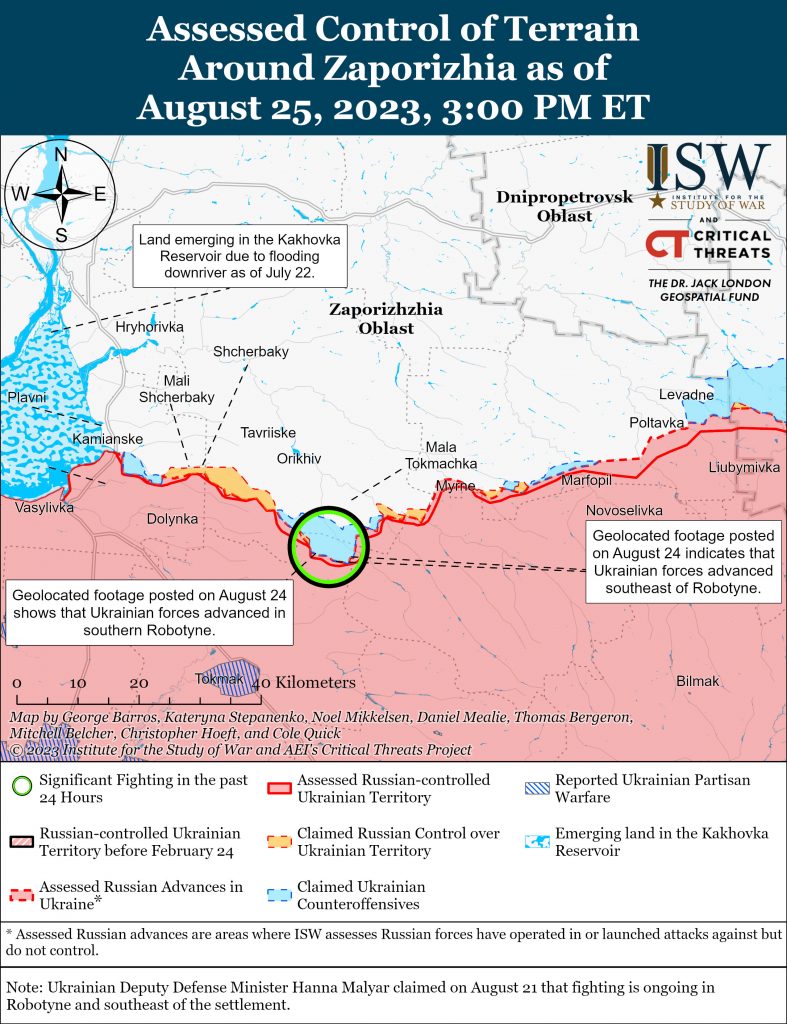

Zaporizhia Battle Map Draft August 25,2023 (Source: Institute for the Study of War)

It’s worth to highlight that Russia taking the city of Bakhmut did not do what many analysts argued it would. It did not crack open Ukrainian lines, and it did not prove to be a key to a further incursion into the greater Donbas, towards Kramatorsk.

Bakhmut’s strategic significance was made up primarily by the fact that both sides had fought so hard for it. It has a psychological importance to this day. Even suffering high casualties for limited strategic value, Moscow probably won’t let it to simply be retaken by the Ukrainians.

It is also worth to highlight the June 6 demolition and destruction of the Nova Kakhovka dam on the Dnipro River. Much of the affected population was on the Russian-controlled bank of the river. Militarily, the breach of the dam temporarily raised water levels affecting Ukrainian forces that set up forward positions on the islands in the Dnipro River. Before the demolition, they had also been regularly launching raids across it into the Russian-controlled parts of Kherson. There were also reports that the main Ukrainian offensive would be through the river with amphibious landing. However, following the breach many of those forward positions were washed away (as were some of the Russian positions and mines on the other bank).

GIF of destruction of the Kakhovka Dam made with Sentinel-2 imagery (Source: Copernicus Sentinel / Wikimedia Commons)

In the short term, the prospect of any Ukrainian offensive across the river dramatically decreased. Some Russian units could also have been redeployed to other fronts from Kherson following this incident as well. In the longer term it is possible that some of these areas that used to be covered by water in the reservoir eventually become navigable by land-based vehicles. But even though the surface in many of these areas is likely to appear dry, the ground underneath is likely to still be soaked for some time. The breach removed a number of Ukrainian military options, inflicted damage on the civilian population, struck a blow to Ukrainian agriculture, endangered the water supply by canal to Russian-held Crimea, and reshaped the geography of this part of Ukraine. But even if the breach did potentially allow the redeployment of Russian forces, or cancelled any planned Ukrainian offensives across the river, it clearly didn’t result in the cancellation of all of Ukraine’s offensive plans.

Moving on to Ukraine’s Main Offensive Thrust

Starting early June, we began to see an uptick in Ukrainian offensive activity, particularly in Zaporizhzhia. Here most of what we’ve seen are been probing attacks carried out at a relatively small scale, small groups of infantry or armoured vehicles attacking fortified Russian defensive positions. It also provided an opportunity to see for the first time some more of the Western equipment that Ukraine had received over the last several months. This is also the phase where the Russian Ministry of Defence started to claim the destruction of Leopard 2 tanks and other pieces of Western military equipment.

It is worth noting, that contrary to some expectations, it is indeed possible to take out Western tanks as well. This has already occurred in Syria, during Turkey’s offensive against Kurdish forces, with the Kurd’s using old soviet-origin weapons. However, the fact remains that even when an anti-tank missile successfully hits a Leopard, the chances of the crew surviving is far greater than inside an old Soviet/Russian equipment. This remains especially valuable as there are limited number of soldiers in Ukraine who have trained on Western equipment.

Concerning the offensive, so far, we haven’t seen Ukraine commit directly to any single geographical objective. Instead, we’ve seen pressure applied at different points all along the front.

However, the most obvious direction of advance would seem to be due south through Robotyne towards Tokmak. On one hand this is probably the line of advance that faces the most extensive Russian fortifications and defences. On the other hand, it also represents the most direct path possible towards the valuable objective of Tokmak, Melitopol and perhaps Mariupol to cut the above-mentioned land bridge. It is also the place where the Ukrainian attacks have received some of the stiffest resistance. Many of the Leopard tanks and Bradley infantry vehicle losses are from this line of advance.

In response to Ukrainians taking territory, the Russians have been launching a number of less-publicized but powerful counter-attacks to try and reclaim positions. In other areas of the front, for example in the north-east along the Svatove-Kreminna line, we’ve seen Russian units go onto the attack and taking limited territory. Their goal as well is to stretch Ukrainian forces.

It appears that a lot of the Ukrainian effort during their offensive is yet directed towards the seizure of territory. Instead, the focus is on counter-battery battle. This means that the Ukranian artillery, instead of hitting forward Russian positions, try to eliminate enemy artillery positions.

This is made possible by the more accurate western artillery and radar systems, along with the HIMARS. While in the past, we’ve seen multiple hits behind enemy lines targeting ammunition depots, the arrival of the Storm Shadow cruise missiles has made it possible to redirect other systems towards hard targets with the goal of directly aiding the offensive.

Wreckage of a Storm Shadow shot by Russian forces over Ukraine (Photo: Sooryan 101 / Wikimedia Commons)

In terms of understanding the impact that this offensive is going to have, it’s not just important to watch how much territory changes hands, but also what sort of effort both sides are expending and how well they’re likely to be able to maintain that level of effort.

It’s useful to remember how Ukraine fought during the Kherson offensive. At Kherson, while the offensive carried on at the front, Ukrainian strike missions were regularly launched to destroy the bridges across the Dnipro River. The goal of course was to eventually undermine the logistical support for Russian troops on the right bank. Defending a trench behind a minefield without food, ammunition and logistics is difficult. While the Ukrainian attacks didn’t gain a huge amount of ground initially, as the Russian supply situation was placed under pressure eventually we saw a complete and rapid Russian withdrawal from the Kherson region.

All Quiet on the Loud Eastern Front

In terms of evaluating the offensive so far, the first thing to note is that we are still seeing Ukrainian attacks across a relatively broad front, with some concentration around Robotyne. According to different reports, the small settlement was finally taken by Ukrainian forces late August.

At the least, one major Ukrainian objective is to breach the defence line towards Tokmak. Once Ukraine breaches that line, many other positions may be vulnerable to flanking or encirclement, and have to be surrendered.

In terms of pacing, this offensive is certainly many times slower than the most rapid movements we’ve seen. This is not comparable for example, to Russia’s initial 2022 advances and retreats around Kyiv and Kherson, or to the Ukrainian operation at Kharkiv. But it’s certainly faster moving than the Russian offensives around Bakhmut.

The offensive has neither failed, nor has it broken the Russian armies and driven to the Azov Sea with waves of demoralised Russians fleeing before it. It would be fair to say that while the situation on the battlefield develops what will be extremely important are the signals sent politically by both sides. Can the West convince Russia that they are in it for the long haul and that a Ukrainian victory is inevitable however long it might take? Or can Russia twist the battle of attrition and time to favour them? As with the ultimate results of this counter-offensive, only time will tell.

[…] As to NATO, the Alliance is as important as it was during the Cold War, just think of the aggression committed by Russia against Ukraine. […]

[…] The German economy has been stuck for a while, precipitated in part by the surge in energy prices that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. […]

[…] However, no one should be fooled by the hypersonic speed at which Ukraine, which is fighting a life-and-death struggle with the Russian aggressor, is currently moving towards the European Union. Indeed, experience and […]

[…] since Ukraine’s spring counteroffensive failed to bring along any breakthrough, there has been a tension and a very vehement appeal – borderline […]