The Cold War as it lies in common knowledge lasted from 1946 to 1991. Now there is a new one but we cannot pinpoint the exact start of it. Experts believe it can be dated roughly to the beginning of 2018, the time by which the preceding processes had come together in a total, complex system. The US National Security Strategy, published at the end of 2017, already provided a systematic summary of the main global challenger, China, and this is reinforced by the Biden Administration’s Interim Strategy Guidance, published on 3 March 2021. Also in late 2017, the self-conscious proclamation of China’s global great power can be linked to the speech of Premier Xi Jinping at the Chinese Communist Party Congress. What can be expected of China in 2023? How does China’s new Cold War continue?

The world is currently embroiled in “Cold War II” ─ and has been for a while ─ and the path ahead is lined with the geopolitics of nuclear weapons, said Niall Ferguson at a conference last spring. “Cold War II is different, though, because in Cold War II, China’s the senior partner, and Russia’s the junior partner. And in Cold War II, the first hot war breaks out in Europe, rather than Asia. This is a bit like the Korean War was, in 1950, where suddenly discovering that cold wars sometimes run hot, but this time, Ukraine is the battlefield”, Ferguson explained.

One of the most interesting consequences of this war is that all around the world people are going to realize: “We need nuclear weapons, look what the Ukrainians did. They gave them up, and now they are in a terrible state. So the end of the era of nonproliferation is upon us. (…) The world a much more dangerous place than at any time since the end of the last Cold War” ─ Ferguson said.

But in any case, the great power games of the millennium will be played out not in Europe but rather in South-East Asia and the US-China rivalry that is also taking place there.

Among Chinese experts and politicians, there is a widespread accusation against America that Washington sees them as a threat to its status as an emerging power. In fact, the US has shifted its attention from Europe to the Indo-Pacific region in the post-bipolar era. Furthermore, Washington enhances the US military’s position in Asia or bolsters the military capabilities of its allies and partners in East Asia. However there is a stark contrast as since the beginning of China’s reform era in 1978 no actor ─ other than the Chinese people themselves ─ has done more to assist China’s broad economic development than the United States. Open US. markets for Chinese exports, large-scale US investment in Chinese industry, and hundreds of thousands of Chinese students in American universities were all essential to China’s fast-paced growth and technological modernization.

At the turn of the millennium, the “Chinese dragon”, aware of the incredible rate and dynamism of its economic development, moved towards “expansionary development”. After the return of its former colonies (Hong Kong and Macau), China has now established its claim to control Taiwan and the South China Sea. The emergence of this new direction coincided with the rise to power of the chieftains of the Chinese Communist Party from the 2000s onward: Hu Jintao and especially his successor, the increasingly authoritarian Xi Jinping. The US response was to use a strategy of counterbalance and pivot, but this came relatively late in the Obama era.

The delusive sense of total hegemony has made US policymakers and pundits complacent, oblivious to how the empire in the sky is building itself in places as far away as Africa, or as far away as the US backyard, South America. The turnaround in the US elite was made clear by President Donald Trump’s anti-China policy and his bipartisan support for it.

Trump has declared a trade war and a technological blockade against China, initiating economic decoupling. Trump’s rhetoric and measures were adopted and even intensified by the Biden administration, which also sought to organize an international coalition to stop and contain China. Japan-China relations were also characterized by growing mistrust. The initial mishandling of the COVID-19 outbreak, the misguided use of mask diplomacy and the emergence of ‘wolf-fighting diplomacy’ ─ i.e. the more assertive and critical approach of some Chinese diplomats ─ only accelerated the estrangement, and quarantine measures would hamper face-to-face meetings that might have allowed for detente.

China’s Rise To Economic Superpower

China has long played an important role in the global economy and has been the largest contributor to world growth since 2008. Between 2012 and 2016, China’s average annual contribution to global growth reached 30.2% while America’s contribution was only 17.8%, the euro area’s 5.3% and Japan’s 3.8%. Since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, its foreign trade has grown rapidly and by 2012 it was the largest trading country, overtaking the United States.

In the latest episode of the trade push, in autumn 2022 the German government, after a long wrangling, allowed Chinese state-owned Cosco to acquire up to 24.9% stake in one of the four container terminals at the port of Hamburg. The report, noted by the German foreign ministry, said the port investment would “disproportionately increase China’s strategic influence over German and European trade infrastructure” ─ nearly half of German-Chinese trade passes through Hamburg, where more than 500 Chinese companies are present. Cosco also has stakes in the ports of Athens, Rotterdam and Antwerp, and in total has ownership stakes in nearly 100 foreign ports. Why is this interesting?

An American study has suggested that ports owned by Chinese companies can provide logistical and intelligence support to the Chinese navy, even if it is no match for conventional military bases in the event of a conflict. But they are also excellent for espionage, information gathering and scanning NATO ships that stop there.

China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) has grown substantially since the mid-2000s: OFDI flows have increased from USD 20 billion in 2006 to almost USD 200 billion in 2016, and globally China has become the main source of foreign direct investment. At the same time, China’s foreign merger and acquisition activity has surged over the past decade.

The number of Fortune 500 companies increased from 9 to 115 between 2000 and 2017.

China’s economic rise is also having a major impact on the international order. The Belt Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, Beijing will likely gain special relationships with more Asian and African states, and Beijing’s global influence will grow accordingly. But those special relationships are much more likely to serve Beijing by preventing such countries from adopting policies that counter China’s interests, not by encouraging those countries to join an allied effort to harm the interests of the United States and its allies.

China’s GDP already surpassed Japan’s in 2009 to become the world’s second-largest economy. With a growth rate even faster than that of the United States, it is only a matter of time before it leaves America behind and becomes the world’s largest economy. China has also started to catch up in science and technology. China’s development over the past four decades has had an impact on the transformation of power at the global level. Sustainable economic development has allowed China to increase its military spending and has taken steps to modernize its armed forces.

China in the New Cold War: Seeking To Change The World Order

China’s military strategy covers two broad areas: 1) to avoid conflicts in neighboring countries that threaten its territory and stability and to avoid events that deter capital inflow. As a result, after the Sino-Vietnamese war in 1979, also known as the Third Indochina War, there was no direct conflict until the end of the first decade of the 21st century. In all cases, China has been a proponent of peaceful, diplomatic solutions and the building of economic relations. This is true even if threats to invade Taiwan are an almost constant mainstay of Chinese foreign policy communications. 2) At the regional level, the focus of Chinese military and foreign policy in the 2010s has been on Southeast Asia and Japan.

In 2010, the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area was established, encouraging intensified cooperation on a regional scale, and creating the world’s largest common market. Sino-Japanese relations have traditionally been built on historical grievances. Traditionally, the US has been less protective of Japan since Trump’s intervention, and as a result, there has been a marked warming of relations between the two Far Eastern countries.

Gergely Salát, a renowned Hungarian sinologist and pundit, describes China’s military strategy and capabilities in one of his analyses:

The country’s stated aim is to have a world-class army. Developments will focus primarily on the navy and air force, but priority will also be given to areas such as cyber warfare and military space technology. China’s first aircraft carrier was launched in 2011 and now has three and more under construction.

Moreover, nuclear strike capabilities, long considered secondary, are being developed, with the number of nuclear warheads doubling from 350 today to 1,000 by 2027 and 1,000 by 2030. China is still significantly behind the United States in military capabilities, but the gap is narrowing. Beijing’s main objective at present is not to compete with the US in force projection capabilities, but to ensure that any hostile forces are kept away from China. The Chinese military does not have global reach, and although it opened its first overseas military base in 2017 (in Djibouti) and is building military facilities elsewhere, its capabilities away from its borders are limited for the time being.

“By contrast, the US military has 516 installations in 41 countries and bases in more than 80 countries. China has two aircraft carriers, the US has 11. The Chinese air force has ten tanker aircraft to supply over 1,000 fighters, while the US air force has 625 tankers for 1,956 fighters. (These are the figures that define the global presence of the air force, because without air refueling ─ and with two aircraft carriers, which are also negligible in this respect ─ the Chinese air force is simply not capable of carrying out longer-range missions,” says Peter Buda in his comparison of the US military’s capabilities.

Beijing’s Expansion Through Soft Power

‘China: Friend or Foe?’, Hugo de Burgh’s book, published back in 2003, details how and why the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) began to build soft power. Dating back to the turn of the millennium, when the party’s leadership, under the hallmark of Hu Jintao, realized how simple and effective it was to counter the then more visible economic and military superiority of the US. According to De Burgh, the Chinese desire to learn (copy) was also at work here.

European cultural (especially Italian) and technological (especially German automotive) superiority was used as a model for soft power. They set themselves the goal of having these if they were to become a serious power. And once the Chinese have made up their minds, they will not budge until they achieve their goal.

The use of secret services is also typical of the “Celestial Empire” in this area. As an example, a few years ago, the Slovak and Czech intelligence services, in their reports for 2019, named the Chinese intelligence presence in their countries as the most intensive, alongside the Russian one. While the Slovak intelligence service report highlighted that Chinese intelligence was mainly interested in the telecommunications sector, in the Czech Republic Chinese intelligence was particularly active in the Czech academic sphere, according to the Czech intelligence service.

The local Chinese governments hold classes for foreigners in government effectiveness. Some of the pupils are academics and experts, and others are government officials from neighboring states.

Beijing’s goals are largely meant to protect CCP rule from external criticism, rather than to export China’s authoritarian model abroad. China’s approach does not target foreign democracies themselves and is a far cry from Mao’s or Stalin’s support of the communist revolution abroad.

Forced Marriage with Russia

Mark Milley, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, in his speech at the 2021 Aspen Security Policy Forum, described current international relations as a tripolar configuration. Milley identified China and Russia as poles, in addition to the United States. This was a clear indication on his part that a new Cold War, the second in order, is taking place between these powers. The chief of staff described the Chinese threat: “We’ve seen a country in four decades … go from the No. 7 economy in the world to the No. 2 economy in the world,” he said, adding China invested its wealth in a significant military. “Forty years ago, it was a very large infantry that was peasant-based and mostly army. Today, it has capabilities in space, cyber, on land, sea, air, underseas; and they are clearly challenging us regionally.”

“They have a China dream, and they want to challenge the so-called liberal, rules-based order that went into effect in 1945 at the end of World War II. They want to revise it. So, we have a (…) country that is becoming extraordinarily powerful that wants to revise the international order to its advantage.”

China often joined Moscow in international forums to oppose the efforts of the United States and other liberal democracies to pressure countries over domestic governance failures and humanitarian crimes.

Chinese-Russian cooperation on such issues has been strongest in Syria, as the two states vetoed multiple draft resolutions critical of the Assad regime and in Venezuela, where the United States has called for the overthrow of President Nicolás Maduro’s regime.

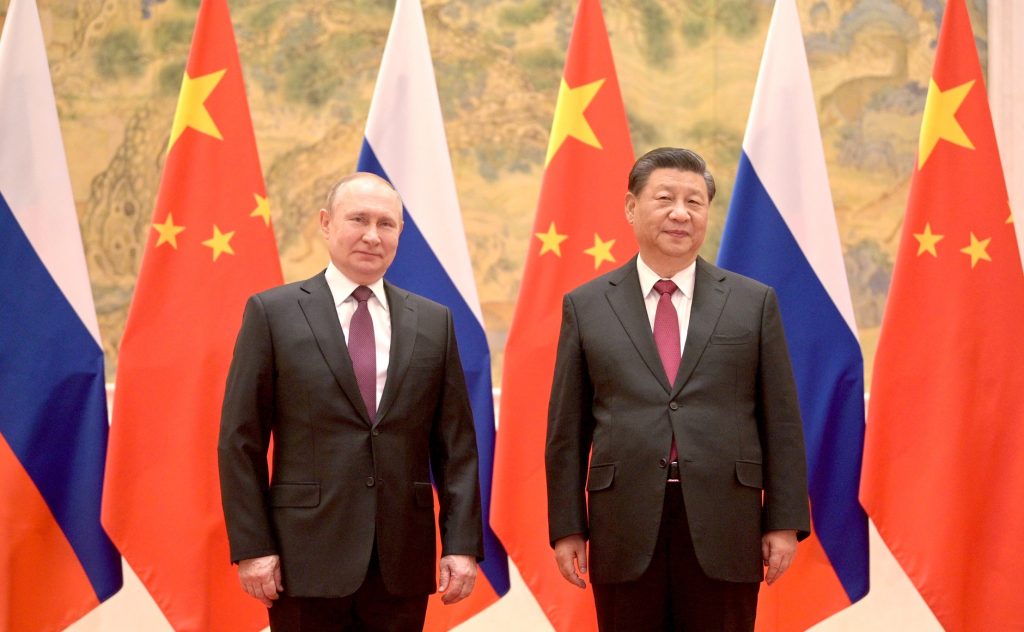

Only three weeks before Putin launched his special military operation against Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the Russian premier and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping published a joint statement on “the dawning new era in international relations”. The text included astonishing claims that Russia and China enjoy “the old traditions of their democracy”. The “Chinese-style democracy” obviously includes the internment of over a million Uighurs, the stifling of democracy in Hong Kong or the daily threat to Taiwan. They called on NATO not to expand in Eastern Europe while condemning the West’s “Cold War” escalation. It was a rather Janus-faced statement to oppose “the unilateral military action by certain minority powers in the international community to solve international problems” ─ even after the Russians were already preparing to attack Ukraine.

It was clear that the strongest binding force between Russia and China was their shared aversion to every US administration’s pursuit of regime change and so-called color revolutions in their spheres of influence.

One of Premier Xi’s new ideas is the “Global Security Initiative”, which aims to transcend the traditional international system based on military alliances and blocs, all of which are aimed primarily at developing countries and seek to transform the Western-dominated world order, to make it multipolar and to break American hegemony. The Shanghai Cooperation, the close relationship with ASEAN, or the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Africa, is based on an understanding of the logic of an interdependent, globalized world, and through them, China is seeking to create a political (and economic) environment with like-minded partner states.

Russian president Vladimir Putin in Beijing with Chinese premier Xi Jinping in 2022. (Photo: kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Sino-Russian relationship does not reach the level of a true alliance. It is hard to imagine direct Chinese involvement in Russia’s struggles with Georgia or Ukraine or any future conflict in the Baltics. Moreover, China is not comfortable with the war in Ukraine. Premier Xi explicitly does not condemn Putin’s war, but if the West were to impose sanctions on Beijing for its possible support of Moscow, the Chinese economy, already in dire condition because of its zero-COVID policy, would be hit hard. Au contraire, China is actually benefiting from Russia’s weakening international position and its growing contempt for a purely Russian sphere of interest in Central Asia. Similarly, it is difficult to imagine Russia taking part in a conflict across the Taiwan Strait or other East Asian maritime disputes.

The Second Cold War: The US Perspective

It is a basic premise that global military presence is necessary to maintain world order. Washington has spent 19 trillion dollars on its military since the end of the Cold War. This is 16 trillion dollars more than China has spent and almost as much as the rest of the world combined over the same period. China’s great advantage is its economic expansion and the large number of countries that trade with it more than with the United States. But if things get rough, the US Navy can currently cut off the East Asian superpower from its trading partners without much effort, and there is little Beijing can do with conventional weapons to counter this. Even if China has the aforementioned nuclear warheads, on the one hand, America has more, and on the other hand, we can see that they are only a deterrent, and no one wants to use them. To address the China challenge, Aaron L. Friedberg sketches in his book imperatives of an American foreign policy that takes the CCP’s Leninism and hyper-nationalist convictions seriously and its world-encompassing ambitions.

First, the US must mobilize the nation for competition with China while firmly distinguishing between the dictatorial CCP and the Chinese people. Second, while decoupling neatly and cleanly from China’s enormous economy is unfeasible, the United States must seek opportunities for “partial disengagement”.

This should begin with blocking CCP efforts to build other nations’ digital and physical infrastructure; thwarting China’s prodigious theft of intellectual property; fostering education, innovation, and basic research domestically; and devising incentives to encourage America and its partners to take more responsibility for vital supply chains and production of crucial goods. Third, the US must revise and fortify its alliance system to counterbalance China in the Indo-Pacific. Fourth, the US must ramp up public diplomacy, not least by finding “leaders who believe in and can explain the virtues of liberal democracy” which, “despite its imperfections is practically as well as morally superior to the alternatives.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping with President Joe Biden at the margins of the 2022 G20 Bali summit. (Photo: White House , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

In Lieu Of Conclusion

As we have seen, military bloc-building on China’s part is not yet on the table. The US, on the other hand, has a positional advantage with the construction of QUAD and AUKUS. Beijing’s only tangible advantage is the undoubtedly very strong anti-Western sentiment, its rivalry with the West. This should not be underestimated ─ but neither should it be overestimated. And in the Third World, the issue was inherently more nuanced: in the shadow of the colonial legacy and the superpower rivalry that accompanied the decolonization process, they viewed the individual blocs with far less confidence. In any case, we can conclude that the prestige of China and Russia in the third world region is currently at an all-time high. As with the Soviet Union in the 20th century, China and Russia are not yet capable of demonstrating a meaningful military force projection capability that even approaches that of the comparable Western (indeed American) capabilities in the 2020s. China does not seem to be willing to give up its own unipolar-based establishment or its alternative global great power agenda to transform the world order. This has created the two sharply opposing poles of the Second Cold War: the US-led Western superpower circle on one side, and some form of China-Russia configuration on the other. The only hope is that the current cold confrontation does not turn into a hot war, that at the present stage of economic globalization and social globalism, the web of interdependencies, it is questionable whether a drastic unraveling of these threads is feasible at all, and to what extent the opposing sides would be harmed.

[…] the most dominant is the strategic rivalry and this will remain so in the coming years as Beijing becomes more […]

[…] “attaches great importance” to the GCI. Under the guise of the war in Ukraine, China is building a new global architecture, an alternative to the Western-led order. Xi’s visit to Moscow has dispelled any doubts […]

[…] is bringing it under the Chinese economic umbrella. Key to China’s appeal is its willingness to dispense with Western-style preconditions such as support for human rights and democracy, as well as a relatively large appetite for […]

[…] right now, Washington is tilting toward a trade war with a country – China – that holds a vast amounts of their bonds. That seems completely crazy […]

[…] this history plays a part in what decisions and alliances are being made today, and […]

[…] Venezuela’s dependence on the United States as their principal export market. Meanwhile, the Chinese tech giants have helped Maduro’s regime in their efforts at internal spying, and (like Russia) China has sold […]