An article by Daniel N. Vig

A world desperate for a clean energy fuel is pinning its hopes on hydrogen, seeing it as a way to power factories, buildings and vehicles without emitting carbon dioxide. Hydrogen has a special place in the universe. It is the most abundant element and has the first place on the periodic table. And when clean energy advocates think about how we can replace fossil fuels, they think about hydrogen. Even the sun is mostly made-up of it. It’s a fuel that when it burns it only emits water. This way, decarbonization through hydrogen is a viable and reassuring thought. Its utilization and future role have been endorsed by the EU institutions, its President and most – if not all – member states. President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen has stated that “clean hydrogen will have a central place in the climate-neutral economy of the future”, while President Macron envisaged that France would aim to become a leader in green hydrogen production by 2030. The path seems to be straight-forward: the EU Commission supports hydrogen production politically and member states implement national Hydrogen Strategies so that we can wave adieu to coal, oil and natural gas.

Underneath the surface however, an entire value-chain needs to be built almost from scratch. This encompasses the production, transportation and the utilization of the molecule.

Currently, only around 10 million tons of hydrogen are produced and sold in the EU, mostly from burning coal or gas, a CO2 emitting energy-intensive process. The transportation is limited to pipelines within industrial clusters, especially in Germany. Furthermore, the majority of hydrogen is used as a component to produce chemical products, ammonia, methanol, and during the defulsurization of oil, production of kerosine, gasoline and diesel.

The Fifty Shades of European Hydrogen Production

The EU only decided on the definition of green hydrogen in the spring of 2022, but it has already set its heart on ramping up the production. The published “Green Hydrogen Rulebook” draft states that the production of green hydrogen must incentivize the deployment of new renewable electricity generation capacity or make use of excess renewable generation that is already online in Europe. This is crucial in order to avoid the displacement of existing renewable generation. Green hydrogen could then be produced by using renewable electricity, such as sun or wind, to power an electrolyser which splits water into its two components: oxygen and pure hydrogen. The hydrogen is collected and transported to consumers, while only oxygen is released as a by-product.

Hydrogen production has other colours than green as well. President Macron has pushed for “pink” hydrogen, which would mean linking France’s nuclear fleet to electrolysers. Nuclear energy would power the electrolysers, which would split water and produce hydrogen. This proposed process would likely put Paris at odds with neighbouring Germany, which is resolutely anti-nuclear. Extensive negotiations are likely, just as it happened during the talks concerning the EU taxonomy. Then, the two sides were able to agree that nuclear energy, which is a national security priority for France, would be labelled as a green source, thus the sector became fit to receive funding from the EU. In the taxonomy talks, the price for nuclear energy was labelling natural gas “green”, a priority for Germany.

Concerning natural gas, presently, the EU produces most of its hydrogen by separating the molecule from methane. This is a process called steam-methane reforming, a mature production process in which high-temperature steam (700°C–1,000°C) is used to produce hydrogen from a methane source (natural gas). This process does emit CO2 and results in “grey” hydrogen, which has adverse effects for the climate. There are however two ways to greenify this process. It’s possible to capture approximately 90% of the emitted carbon and not release it into the atmosphere. This is called Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). Even better for the climate, would be to utilize the captured carbon (CCUS). Both these processes result in “blue” hydrogen.

Lastly, “turquoise” hydrogen is made using a process called methane pyrolysis that produces hydrogen and as a by-product solid carbon, physically tangible. All these processes, grey, blue and turquoise, involve a thermal process, basically heating methane. In order for the processes to respect the climate, heating must be done using renewable energy sources or, at least in Paris’ view, nuclear energy.

Hydrogen as Investment

European companies have been eager to tap into green hydrogen projects, as they can count on long-term financial support from Brussels. In her 2022 State of the Union speech, Commission President von der Leyen announced the creation of the European Hydrogen Bank, which is hoped to be able to invest 3 billion euros to support the future market for hydrogen.

In October 2022, the Commission approved a €1 billion German measure to support the Salzgitter company to decarbonise its steel production by using hydrogen. That same month, the Swedish steel venture H2 Green Steel received 3.5 billion euros in debt financing from Swedish state-owned and commercial banks. Eliminating fossil fuels from the steel-making process could cut Sweden’s total CO2 emissions by at least 10%. Worldwide, steel plants are responsible for 9% of all carbon dioxide emissions, owing to the large quantities of coal in the process.

Hydrogen: The Solution for Transport Decarbonization?

Large-scale consumption of green hydrogen has been projected to take place in heavy duty transport as well. This is a necessity, as marine, aviation and rail consume energy in quantities that exceed what batteries can provide.

Heavy-duty trucks, trains and tugboats are likely to become the first candidates to open the door.

In fuel cell trucks, hydrogen is converted into electrons and water, with the electrons powering the truck’s electric motors. The water is released. Hydrogen tanks also weight lower than batteries, so the trucks as a whole are also lighter and need less energy overall. In railways, the French rail company Alstom has already built the first hydrogen fuel cell powered train for commercial use. It currently runs on German railway and its exhaust is only steam and condensed water.

Debut of the Alstom Coradia iLint, a hydrogen-powered passenger train, at InnoTrans 2016. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Destination Rotterdam

The port of Rotterdam has put in place a concrete plan for hydrogen production along its shores. The stated goal is to produce 4.6 million tons of hydrogen annually by 2030. This would mean that Rotterdam alone would produce 46% of the 10 million ton EU hydrogen production target set by the European Commission.

In this project, the operator has plans to build electrolyser units near the shore, which would be powered by offshore wind facilities.

Since the renewable energy source and the electrolysers would be constructed relatively close, there would be minimal loss of energy in the connection. The produced hydrogen is to be transported via pipeline to the industrial Rhine region of Germany, the Port of Antwerp and the rest of the Netherlands. Large multinational companies, such as Shell, BP and the German RWE group are taking part in the project. The Rotterdam project is likely to serve as a point of reference for future European H2 investment and its success is crucial.

Russia Heaves in Sight… and Ukraine

Apart from hydrogen production inside the Union, the European Commission set a target that by 2030 the EU should import 10 million tons of green hydrogen annually from third countries. Interestingly, before the war, President Putin stated that Russia can turn into one of the world’s largest hydrogen producers and exporters by 2035.

Russia’s potential lies in the production of blue hydrogen, separating hydrogen from methane and capturing the carbon.

The pipelines which until recently transported natural gas could, in essence, be repurposed to transport hydrogen. In January of last year, in a bid to avert the war, Germany’s Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action Robert Habeck even stated that Germany and Russia should start cooperation in renewable energy, including hydrogen. Naturally, in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, any new kind of cooperation related to energy with Russia is implausible.

Even before the conflict, Russia’s energy policy has had profound consequences for Ukraine. The Turkstream natural gas pipeline that Russia commissioned in October 2021, along with the NordStream 2, bypassed Ukraine. Hungary started to receive the majority of its Russian gas through Serbia. The two pipelines – one in the north, the other in the south of Europe – meant that Ukraine lost valuable transit fees, which have been crucial for its economy for decades. To compensate the financial hit, Germany and the USA published a joint statement detailing support for Ukraine, European energy security, and climate goals. In it, together with the US, Germany committed to a $1bn Green Fund for Ukraine to compensate the annual revenues of $2bn of transit for Russian gas. This, along with the designation of a special envoy from Germany with dedicated funding of $70 million to renewables, were the offers that Germany made to mitigate the negative financial effects of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline for Ukraine.

Ukraine has 31 billion cubic meters of storage facilities for natural gas, which is equal to 8% of the EU’s annual gas consumption. This, in practice, could be retrofitted to store hydrogen.

Seeing this potential, German multinational energy company RWE signed a memorandum of understating with Naftogaz, the state-owned Ukrainian oil and gas company. The agreement covers the production and storage of green hydrogen and ammonia – a potential renewable synthetic fuel – as well as their export from Ukraine to Germany. With political support from Berlin, German companies have started to explore the massive eastern energy market.

If, at the end of the war, Ukraine remains sovereign, keeping the majority of its territory, the potential of wind energy in the country would make it able to produce a large amount of renewable energy, and perhaps even green hydrogen.

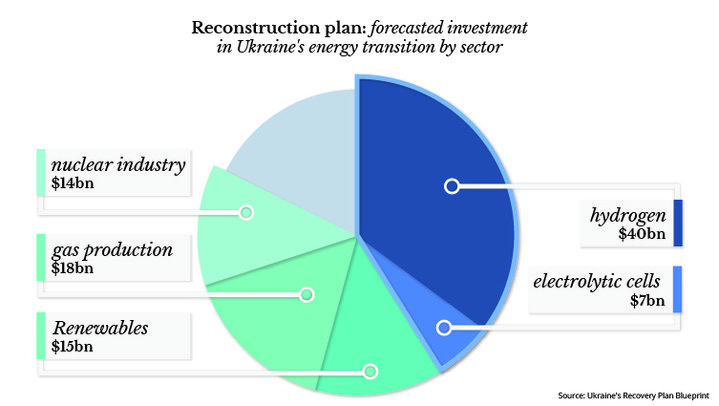

The already existing pipeline network of 90 billion cubic meter capacity in Ukraine could make it possible to transport hydrogen to the central European countries. Eustream, the Slovakian natural gas transmission system operator (TSO), already joined an initiative which envisages the transportation of Ukrainian green hydrogen through its existing pipeline network to Germany and Austria. Furthermore, Ukraine, keen to join the West politically and economically, has calculated with hydrogen in its post-war energetical reconstruction roadmap as well.

A Mainstay in EU Package Deals

Europe has also pushed hydrogen into almost every major energy infrastructure cooperation since the launch of the Green Deal in 2020. Electricity from green hydrogen in Azerbaijan, pipeline transporting hydrogen from Algeria have been agreed upon. Angola is set to become Germany’s first supplier of green hydrogen as well. A less-publicized detail in the media is that most of these deals are Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs). In essence, this means that they do not have to contain legally enforceable promises. There are no repercussions if the parties don’t follow through.

Shiny Future, Bleak Present

Whenever green hydrogen import and production is mentioned, it’s better to take it with a pinch of salt. Currently, 98% of hydrogen is made from fossil fuels. That’s grey hydrogen, the worst for the climate. No one is certain how much hydrogen – if any – can be transported in the existing European natural gas pipelines. Studies have proven that the household heating sector will not use hydrogen. It’s too inefficient and expensive. Hydrogen fuelled vehicles have been around for decades (even Jack Nicholson promoted it in 1978), but they haven’t lived up to their potential. What we’re witnessing is an energy revolution with a top-down approach.

Europe won’t use hydrogen for all the things the politicians say it’s capable of. Nevertheless, it will play a role in key sectors, shaping the future of energy security. Europe will store excess renewable electricity generation in hydrogen. Ports will be the first major transportation infrastructure to decarbonise. Clean hydrogen is the only molecule capable of decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors, such as steel. Last but not least, Europe will base new energy partnerships on hydrogen. Without Russia.

Daniel N. Vig is an energy policy expert having recently worked for Hungarian governmental energy policy institutions including being an analyst for Hungary’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. With an eye on the security policy implications of the sector he is also a former NATO Project Assistant.

[…] momentum is strong. Currently, Europe has 117 billion USD worth of hydrogen project-proposals. That’s 35% of the global investment. 7 billion USD has already been committed in Europe. A large […]

[…] we have launched our 3W initiative to support the implementation of projects in the field of water, hydrogen and carbon,” she stressed in the closing of her […]