Poland, in the last 7 years, has been the bastion of European conservatism along with Hungary. The Law and Justice party (PiS from now on) has been the party that has carried out all the conservative policies in Poland. It has also been the standard bearer for right-wing forces in Europe, something that became a struggle between the European Union and Poland. Therefore, Hungary and Poland have been great allies, not only because of historical facts, but because of their similarities in national policies and how they saw the European Union’s present state. Now, Hungary will be a bit more alone, even if there are new conservative governments in Europe. The relationship between Poland and Hungary was very close, even if the war in Ukraine cooled it down.

All this has changed, as on October 15, 2023, elections were held in Poland to elect members of Parliament (Sejm) and the Senate. The official results were 194 seats for PiS; 157 for the social-democratic Civic Platform (PO), 65 for Trzecia Droga (Third Way), a center party; 26 for Lewica, a left-wing party, and finally 18 for the right-wing Konfederacja.

The absolute majority in the Sejm is 231 seats, a number that for the first time in a decade PiS fell far short for, even adding the seats of what would be its natural partner, the Konfederacja. However, the union between PO, Third Way and Lewica gave a surprising number of 248 seats.

To find out what happened, The Long Brief interviewed Ugo Stornaiolo. Stornaiolo is lawyer and he’s a visiting LL.M. student at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, the Catholic University of America and the Université d’Orléans in France, as well as a former research fellow at the Mises Institute. He authored the book Jueces como Soberanos, a constitutional law critique of judicial review excesses in Ecuador, and is currently associate editor for The Miskatonian, contributing editor for The Libertarian Catholic, and international correspondent for Navarra Confidencial.

After many polls, do you think this result was what could have been expected?

Honestly, yes. People don’t get to consider that Polish society is not monolithic in their beliefs, but rather very diverse, which added to the highly decentralized nature of the Polish state and of Polish politics, makes any “national” strategy ultimately meaningless. PO’s stronghold is in what is locally known as Poland A, the former Prussian/German partition, more progressive, more industrialized, more urban, like Silesia, Trójmiasto, Wielkopolska. It also happens that Plataforma Obywatelska is more Germanophile in their politics and their external influence.

PiS has higher support in Poland B, the former Austrian and Russian Partitions, internally seen as “backwards” by the local progressive intelligentsia, but culturally more Catholic, more conservative, even if not as economically developed as the West. That’s on a global perspective. In practice, big cities in Poland B tend to be battlegrounds for votes, with PO gaining strength there, while PiS have kept their influence on the countryside. Blame demographics and the European influence in urban-educated youths for the changes in the general voting patterns.

Ugo Stornaiolo

What do you think went wrong with PiS’s strategy for losing the election?

PiS has many, many issues, and any educated conservative Pole would agree. First, they are really bad on their economic policies. Some analysts like Franco-Polish Daniel Foubert would disagree, but the general perception is that PiS is for the blame with current inflationary problems. For the everyday Pole, inflation is quite bad and there might have been a rise in general living costs, even if of the external bystander it’s not that bad. It also happens that currency exchange rates are quite volatile even if stable between the 4 to 5 zloty per USD or euro. It doesn’t affect much on the macro, especially foreign investors, but makes a lot of trouble for the working classes.

Then you have the cultural alienation. PiS is not officially a clerical party, but has a lot of internal elements that called for further increases in Catholic influence in policy. The former Justice minister, Zbigniew Ziobro, for instance, the architect of the very controversial judicial reform, is an open integralist and has publicly endorsed Catholic integralism and the Social Kinship of Christ as leanings PiS should adopt. There’s also plenty of Church scandals that have been either related to PiS or covered by PiS officials, so when you take all of this together, you create an image that young, Europeanist progressives will reject, especially since that also means rejection of gay marriage, abortion, feminism and contraception.

PiS knows their voters, but doesn’t know their opposition, and just describes the stereotype as the ridiculous image they already think of the opposition. That doesn’t win elections but rather alienates potential young voters.

In most polls, Konfederacja had a projection of between 9 percnt and 10 percent, but they have not reached that threshold. What do you think could have gone wrong?

Konfederacja is an interesting case, even in the diversity of European politics. First, because they’re a big tent alliance, but exclusively of right wing parties and movements. They are very selective on who’s inside, and you won’t find any form of left leaning ideas or movements inside. Everyone is right wing, some even more right wing than others. Just as a matter of example, Konfederacja has an openly paleolibertarian party, Nowa Nadzieja (New Hope), which was the former KORWiN movement (led by polemicist Janusz Korwin-Mikke), an openly monarchist movement, the titular Konfederacja Korony Polskiej, which is also openly Catholic and traditionalist, and the nationalist Ruch Narodowy, which follows a similar line to the French Front National back in the days of Jean Marie Le Pen.

All of these movements within Konfederacja have one issue that has prevented them for earning further support, and that is that they do not support the war in Ukraine.

Both PiS and PO are very much aligned with the Western/NATO position when it comes to the war supporting the Ukrainian effort, but Konfederacja is one of the dissident voices, which has earned them a reputation of being pro-Russian, and some of their leaders (like Korwin back in the day, or now Grzegorz Braun, who recently disrupted a Hanukkah celebration in the Sejm, getting accused of antisemitism in consequence) of being Russian agents.

That’s not new, and both Tusk and Kaczynski (respective leaders of PO and PiS) have accused each other of being Russian agents, particularly in regards of the death of Kaczynski’s bother Lech (former president of Poland who died in office), but the truth is that neither of them are aligned with Russia (PO more aligned to Germany, PiS to the US).

With Konfederacja, that’s how most people outside their sphere consider them, and voters do not take that lightly. You wouldn’t vote for a movement widely considered to be pro-Russian if all of the country is united in supporting the current enemy of Russia, which is Ukraine.

It also happens that Konfederacja leaders usually mess up immediately before the election with some controversial statement regarding women’s rights, gay people or something along the lines of progressive groups and the culture wars. Korwin used to be quite fond of doing so, and now his successor Mentzen has taken up his habit. That tends to alienate a lot of potential voters right before election day. Some commentators have jokingly called this the 6 percent protocol, because that’s the threshold needed to keep registered as a party in Poland, and usually what Konfederacja gathers at most, but nothing more, just because of these controversial statements.

According to the latest polls, Lewica, the Polish left, has been the second most voted for party among young people. What could be the reason?

Lewica is another one of those Central-Eastern European rarities, since the Soviet Communist memory is still strong and very much rejected. They are not socialist per se, but rather progresisve altogether.

They might have some democratic socialist leanings, but most of the groups within Lewica are New Left, ideologically.

Feminism, ecologism, gay rights, Europeanism. They take the flag of the cool left from the developed world (that is, the rainbow flag) and raise it as their banner. And young university educated students, deep in the European dream that has merely arrived to Central-Eastern Europe (it’s already dying in Western Europe), with all their Erasmus experiences of freedom (free travel, free love), they tend to equate “Europe” as a political project with progressivism. And Lewica offers them that option. So naturally, they support them.

Was the reason Mateusz Morawiecki was appointed Prime Minister in case there was any chance that the PSL (without Third Way) would give its votes to form a tripartite government composed of PiS-PSL-Konfederacja?

The appointment of Morawiecki as PM for a third term was a gambit by President Andrzej Duda to try to win time and gather support to keep PiS in government despite the backslide in the last election’s results. Duda, Morawiecki, and most importantly Kaczynski likely knew that the situation was not going their way, so they tried to play one last trick before yielding power, mostly trying to win over independents with Cabinet appointments, but that didn’t turn out well.

PSL, the agrarian Polish People’s Party, is currently one of the members of Trzecia Droga, the Third Way Coalition, alongside Poland 2050. They are neither left nor right wing leaning, but tend towards a more classical Christian Democratic position (think of the former Catholic Zentrum in Germany).

PSL formed part of coalitions governments with PO back in 2007-2015, so they are mostly seen as proxies for whatever policy Tusk will propose and implement.

Poland 2050, however, is more interesting, since it was founded by a Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s wannabe, Szymon Holownia, who pretty much lacks any ideology except for a watered down, safe-for-TV-networks form of liberal democracy (which explains what exactly Poland 2050 stands for, and that is pretty much nothing but whatever Brussels will say) and who happens to be just good enough for the democratic game. It worked for him since he gathered more than half of the votes for Trzecia Droga and thus allowed him to negotiate with Tusk for parliamentary support for a vote of confidence in a PO government. He was also critical of the Morawiecki government since his days as a TV personality, so any support for a PiS government would probably have been non-existent.

Szymon Hołownia with Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz at a press conference in the Senate (Photo: Tomasz Kaczor / Wikimedia Commons)

At last, Konfederacja prides itself in being the independent right, not only separate from PiS but many times also in direct opposition to them, considering them too socialist for their free market/low taxes/low public spending tastes. There was absolutely no chance any coalition government with Konfederacja and PiS together would have happened, even for the most wishful thinking.

With the opposition government, what will be the first internal policies that will change?

Tusk’s cabinet is not a PO cabinet, but a coalition cabinet incorporating members of PO, TD and Lewica. While PO is more centre right, TD is non-ideological and Lewica is hardline progressive. While ultimate decision power will be in Tusk’s hands, he also gave strategic ministries to Lewica members, like Krzysztof Gawkoski, who’s deputy PM and holds the digital affairs portfolio, or Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk or Barbara Nowacka, who will head the Family and Education ministries, respectively.

From this alone, we can see that Tusk yielded the cultural element in his policy plan to Lewica, and they’ll try to push their progressive agenda as much as possible.

The rest of traditionally strategic portfolios, like foreign affairs, now headed by Radoslaw Sikorski (Oxford alumni, former war correspondant in Afghanistan, and husband of neocon darling Anne Applebaum) or justice, now headed by former ombudsman Adam Bodnar, are in PO’s hands, so that’ll change Poland’s position in respect to the European Union, particularly in their judicial clashes, but keep it in regards to the war in Ukraine.

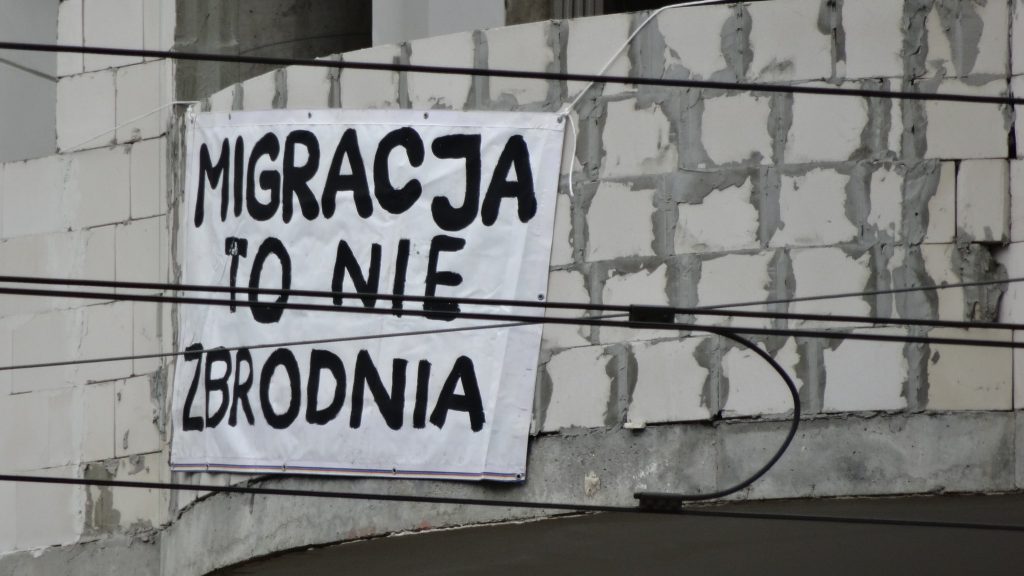

Will there be changes in immigration policy?

That’s a hard question, because one of the strengths from the former PiS government was their strong stance against illegal immigration and asylum seekers from Middle Eastern countries. This is seen outside of Poland as a zero tolerance policy against all migrants altogether, but as an expat myself, I can bear witness this is not true. Poland is quite open for other EU citizens to come and make a living here, has a good population of legal African and Middle Eastern immigrants, and has been the largest receiver of Ukrainian refugees since the start of the war, not even since 2021, but since 2014.

Poland opposed the EU’s migration pact during the last months of PiS in power, and if history shows something, is that the last time PO tried to yield to the EU in immigration policy, back when PO was in government in 2015, PiS mobilized the population in the urns and got into power. Tusk might not be as reckless this time if he wants to keep in power longer than circumstances might allow him to.

But that’s ultimately not to him but to his overlords in Brussels. PiS benefited from a lot of freedom from DC in their internal policy as long as they complied with NATO guidelines on how to handle with the Ukrainian issue. But with PO in power, that may be quite different now.

“Migration is not a crime” written in Polish on a sheet in the street (Photo: yesfuture / Flickr.com)

With the opposition government, what will change in its position within international organizations, such as the European Union, Visegrad and NATO?

Poland’s new foreign affairs minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, from PO, is quite the Anglophile. Oxford educated and married to Anne Applebaum (American born, Pulitzer prize winner, staff writer for The Atlantic, and overall Russia, formerly just Soviet, hater and Donald Trump disliker), Sikorski already served as foreign affairs minister from 2007 to 2014, strengthing ties with both France and Germany as Poland’s EU senior partners but also with Russia, where we has frequently hosted by his counterpart Sergei Lavrov.

Ministers Lavrov and Sikorski in front of the MFA’s Przezdzieckis’ Palace in Warsaw in 2010 (Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland / Flickr.com)

He also dealt with strengthening relations with the US and with NATO and with mitigating the waves from the Euromaidan protests in Ukraine in 2014 in Poland. After a brief stint as Marshal of the Sejm in 2015, he was awarded with a fellowship in Harvard, and let went on to become a member of the European parliament between 2019-23, right at the start of the current phase in the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Just from his CV, we can clearly see his leanings towards closer integration with the EU (mostly German-led) and NATO (under US command) rather than with the closer Visegrad countries.

Let’s remember that the Visegrad Group, in its current form at least, as well as the expanded Three Seas Initiative and the Lublin Triangle with Lithuania and Ukraine, have been developments made by PiS officials under PiS governments. Poland under PiS was also the prime partner of Hungary in opposing EU progressive policy in gay rights, family law and education, which made them cultural pariahs for the liberals but underdog darlings for conservatives. I can safely assume that Sikorski’s foreign policy will follow PO’s overall Europeanist/NATO view and simply kowtow to whatever cultural and military guidelines that come from Brussels and DC as long as there’s money from the ECB in Frankfort and from the US Federal Reserve.

Will Ukraine’s support remain the same or will there be any changes?

Ukraine is a strategic asset in both US, EU and national Polish foreign policy. Everyone has stakes in the war and in Ukrainian victory, or at least in a stalemate that leaves most of Ukrainian operational for investment purposes. If you remember Huntington’s theory of clash of civilizations, Ukraine is currently a buffer state between Eurasia and the (Angloatlantic) West.

Both Russia and NATO have interest in conquering Ukraine, either through political culture or military might so they can further advance into their rival’s borderlands.

For the US and the EU it means showing the rest of the world the West is not in decline and it can still hold the (Reagan ideal) of liberal primacy through reason or force. For Poland, it means historical vindication from the losses against Russia during the partitions. This is not public policy but political culture that both PiS and PO agree on.

Ask any Pole if Lwow is more Polish or Ukrainian, at least culturally speaking, and you’ll understand.

The war in Ukraine is a matter of national policy in Poland for historical reasons. The formal justification might be national security, and the concerns are understandable, but Poland is not yet in danger, and it might not be in a while. I think a stalemate is the ultimate end scenario for everyone and Poland will have it’s symbolic victory as long as they receive a status they were denied at the end of World War II, which is that of winning power.

Finally, Duda, President of Poland, has the ability to veto laws, do you think he will use this veto often or will he let Donald Tusk rule?

Many people think that Duda will be the main counter to Tusk’s exercise of power while in office, mostly because it reminds them of the situation in the early 2010’s when Tusk was PM and the late Lech Kaczynski was president, also from PiS, like Duda.

In the constitutional design of the III Rzeczpospolita Polska, the president holds veto power over legislation and thus can prevent any bill from becoming law, although that power is still contrained by constitutional limitations.

The start of Tusk’s premiership is already marked by conflict with Duda since Duda signed in May, still under a PiS government, the so called Lex Tusk to allow for investigations of Russian interference in Polish politics, based on the previously mentioned accusations by PiS members of Tusk and PO being Russian agents.

Nonetheless, I do not think Duda might be the biggest obstacle for Tusk to rule as he pleases, and that’s because of another feature of the III Rzeczpospolita Polska: the Constitutional Tribunal. As it happens in many other countries, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal holds near sovereign judicial review powers and can actually strike down any laws according to their own interpretations of Polish constitutional law.

Most political analysts tend to forget or disregard this aspect but most of the conservative wins in the Polish cultural struggle under PiS have not happened in the Sejm nor in the urns, but in the Constitutional Tribunal.

The abortion ban, the anti-LGBT zones, the immigrant quota ban have all been subjected to judicial review and been upheld as constitutional by the Polish Constitutional Tribunal. It should be worth mentioning that its current president, Julia Przylebska, is a protégée of Jaroslaw Kaczynski’s and frequently commuted with him during his tenure as deputy PM and unofficial Chief of State, so her political (and ideological) allegiances are not unknown.

Tusk might try to propose or push for reforms to adjust to his project but as long as neither Duda’s nor Przylebska’s positions are threatened, he might find strong opposition in both potential presidential veto and judicial review.

He will have to play it cool with both and not force anything he cannot back with enough political stregy, either internal in the Sejm, or external from the EU.