An article by Ashley S. Deeks, University of Virginia

The details are disputed, but either way the result was the same: On March 14, 2023, a U.S. drone crashed into the Black Sea after an encounter with Russian aircraft.

According to the U.S. version of events, the unarmed MQ-9 surveillance drone was flying in international airspace when two Russian fighter jets dumped fuel on the drone before colliding with it in violation of international law.

The Russian Defense Ministry denied that its aircraft made contact with the U.S. drone. Instead, Russia asserted that the drone was flying in the direction of Russia’s borders with its transponder off, suggesting that Russia found the flight suspicious.

In addition, Russia said, the U.S. drone violated the “temporary boundaries” that Russia had established for its operations against Ukraine and crashed on its own.

In light of Russia’s past misrepresentations about its military activities during its invasion of Ukraine, I view Russia’s assertions with skepticism. Moreover, as someone who studies international law and formerly served in the U.S. State Department as a lawyer advising on issues related to armed conflict, I see this episode as highlighting the right of countries to operate aircraft and drones in international airspace – even for the purposes of spying on another state.

Showing ‘due regard’

If the U.S. characterization of the facts is correct, then Russia did indeed violate international law by interfering with the U.S. drone.

Under Article 87 of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Seas, the high seas – basically, waters that are not any country’s territorial sea or exclusive economic zone – are open to all states. And the right of a country to operate on the high seas includes the freedom of overflight.

The convention also states that the freedoms “shall be exercised by all states with due regard for the interests of other states in their exercise of the freedom of the high seas.”

The United States is not a party to the convention, which was signed in 1982 and currently has 168 parties, including Russia.

Nevertheless, the U.S. recognizes many of its provisions as customary law; indeed, a key U.S. naval handbook recognizes that “the aircraft of all states are free to operate in international airspace without interference by other states.”

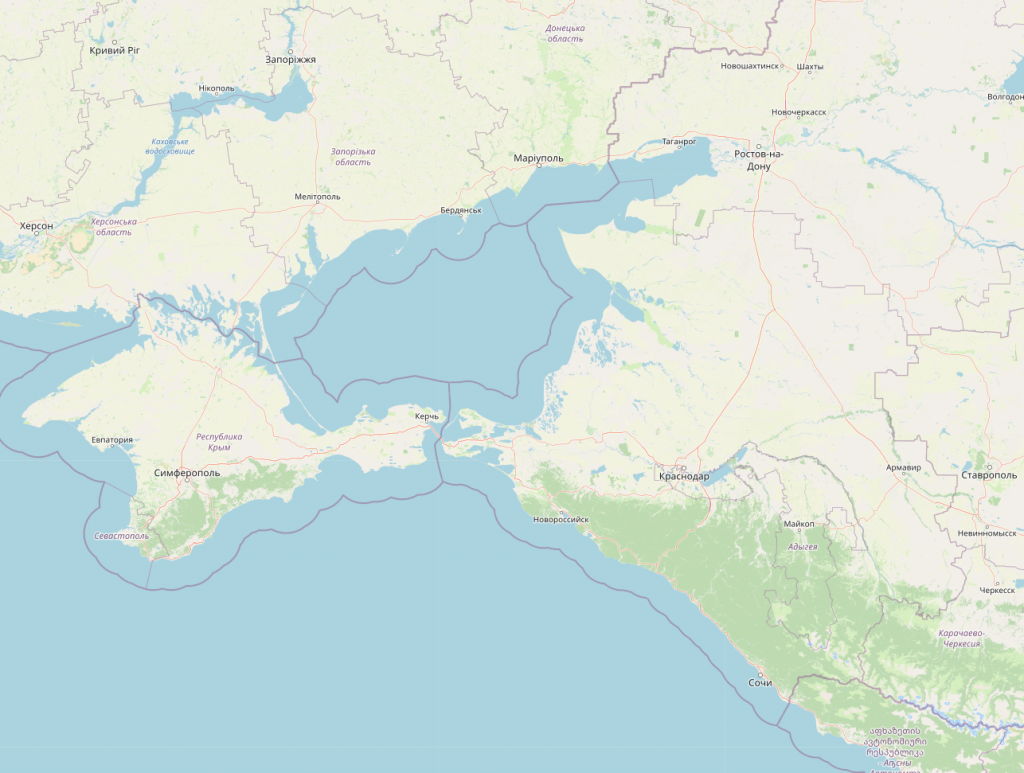

Portion of the Black Sea with international waters in the middle. (Source: OpenStreetMap)

As such, Russia violated international law when it failed to act with “due regard” for the U.S. right to engage in freedom of overflight. In fact, based on the U.S. account, Russia directly interfered with that right. And it is presumably on this basis that the State Department spokesman called the drone’s downing a “brazen violation of international law.”

Any Russian concerns that the U.S. drone may have been spying on its military operations would not alter this conclusion.

Freedom of overflight in international airspace includes the act of monitoring activities inside another state’s territory, as long as the monitoring occurs from within international airspace.

So it would not matter from the perspective of international law whether the United States was using the MQ-9 to spy on military activities inside Russia or Russian-controlled Crimea.

Aircraft in conflict zones

Russia appears to be taking the position that it was entitled to set up boundaries for its “special military operation” in Ukraine and that the United States disregarded those boundaries.

Russia may be referring here to a “maritime exclusion zone” that Russia set up in February 2022 to prohibit navigation in the northwest portion of the Black Sea.

In general, the United States considers such zones to be lawful if their purpose is to direct neutral ships and aircraft away from conflict areas – they can play an important role in reducing the risk that such vessels are mistakenly attacked. The United States itself established a “maritime safety zone” in the Mediterranean Sea in 2003 in connection with its invasion of Iraq.

However, neutral ships and aircraft do not become lawful targets merely because they enter such zones.

Russia would only have had a reasonable claim to use force against, or interfere with, the U.S. drone if it posed an imminent threat of an armed attack or was otherwise a legitimate military target during an armed conflict. For this to be the case, the U.S. drone would have had to be taking direct part in hostilities, and it is known that the MQ-9 was unarmed.

On solid ground in the skies

Assuming the U.S. account is correct, it would not be the first time that a country has interfered with a U.S. surveillance aircraft in an unsafe manner and effectively downed it.

In 2001, a Chinese fighter jet bumped into a U.S. signals intelligence aircraft that was operating 70 miles from China’s Hainan Island. The U.S. aircraft was damaged in a way that forced it to make an emergency landing on Hainan, while the Chinese fighter jet itself crashed. At the time, the United States asserted that international law, including the “due regard” principle, permitted the United States to conduct surveillance flights in China’s exclusive economic zone, which the U.S. considered to be international airspace. China didn’t and detained the 24 U.S. crew members, demanding an apology from Washington.

Since then, China has intercepted Australian and Canadian aircraft that were engaged in routine surveillance in international airspace, prompting complaints similar to those the United States is making now.

In both the China case and the recent Black Sea incident, the United States has taken a consistent, widely shared position on the use of international airspace. As such, I believe it is on solid ground in objecting to Russia’s actions as unlawful.![]()

Ashley S. Deeks, Professor of Scholarly Research in Law, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.