While attention is focused on the wars in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip, the militarization of the South China Sea continues. This year, China expanded its territorial claims over the region, prompting responses from several countries and India and Australia in particular, following the release of a new map in August. Furthermore, the significance of the South China Sea is heightened by the fact that the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza pose threats to China’s strategic interests.

Security spillover is a reemerging concept of international politics. While it is often identified as a regional spread of a military conflict, in the era of toxic interdependence, assertive great powers, and drastic wealth inequality makes it a global phenomenon. Academic discussion in East Asia is heavily focused on the aftermath of the Ukraine war, and the conflict in Gaza. Russia’s attrition warfare in Ukraine has a direct effect on the balance of power in North-East Asia. North Korea is a main weapon supplier for Russia, providing financial support and advanced bargaining positions for the dictatorship. India, on the other hand has lost a historic moment due to the outbreak of the Gaza crisis. The India Middle East Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), often compared to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was announced on the G20 Summit in September. Partners of IMEC, including the European Union, France, Germany, India, Italy, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the United States, proposed a plan to construct two corridors of rail connections, electrical and data cables, as well as pipelines designed for hydrogen export.

The announcement initially indicated progress in the negotiations for Saudi-Israeli normalization. However, the onset of the Hamas-Israel war on October 7 has shifted the focus away from this issue. Establishing new economic and political ties between Israel and the Middle East is now significantly more challenging. Tensions are particularly high in Israel-Jordan relations. Demonstrating potential complications, the participating countries failed to organize a meeting within the stipulated 60 days to formulate an IMEC “action plan,” as outlined in the G20 announcement.

The Chinese Nightmare

As the examples of North Korea and India demonstrate, security spillover manifests in a more complex manner in another relationship when there is an intricate interconnection between conflicts and the involved parties. It follows that the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East particularly impact China. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched in 2013 essentially aims at the integration of the Eurasian region.

However, the two, armed conflicts are situated along cultural central lines of the two continents, highlighting the limitations of such objectives. The violence, especially in the case of the BRI’s land component, the so-called Silk Road Economic Belt, disrupts the integration process.

The ‘Belt’ component of the Silk Road Economic initiative pertains to the envisioned reconstruction of historic overland trade routes connecting Europe and Asia. This ambitious project is intended to be predominantly developed with Chinese expertise.

However, the war unfolding in Ukraine poses a significant risk to Chinese ambitions.

Uncertainties surround the viability of both the direct route from Changsha in China’s Hunan province to Chop in Western Ukraine and the Xian-Budapest line, which traverses Kyiv.

Additionally, several Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries are ally of NATO and a member of the European Union, thus has assumed a crucial role in facilitating the transfer of weapons to Ukraine, has welcomed more than 2 million Ukrainian refugees.

Vladimir Putin welcomes Xi in Moscow during Xi’s visit to Russia in March 2023 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Kremlin.ru)

The perceived tacit support from China for the Russian invasion is likely to diminish the willingness of these CEE countries to enhance cooperation with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). At the same time, Chinese investments in Ukraine are experiencing the consequences of an enduring and violent conflict.

In the Israeli conflict, China’s position is even more problematic. Peace and security in the Middle East is an existential issue for Beijing.

China, the second-largest economy globally, has rapidly developed a reliance on foreign oil. Currently, approximately 72 percent of its oil requirements are fulfilled through imports. China also stands as the leading purchaser of oil from Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-largest producer after the United States. Approximately half of China’s oil imports, and slightly over a third of the total oil consumed in China, are sourced from the Persian Gulf. China has increased its oil purchases from Iran, a longstanding supporter of Hamas, the group responsible for the attack.

Over the past two years, China has more than tripled its imports of Iranian oil, accounting for 87 percent of Iran’s oil exports last month. Officially, China does not admit to procuring any oil from Iran, but industry experts have documented the purchases.

Therefore, the two conflicts simultaneously block the Central-East European trade corridor and jeopardize China’s energy imports.

This further underscores the significance of maritime trade routes, especially the South China Sea. The question arises about the impact of the violence in Ukraine and Israel, specifically in the Gaza Strip, on the already precarious security situation in the South China Sea. This region serves as a crucial passage for a significant portion of China’s energy imports, estimated to be around 70 percent according to some analyses. Additionally, the South China Sea possesses untapped energy resources. Moreover, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) estimates that approximately 20 percent of worldwide maritime trade and 60 percent of China’s trade activities pass through the Malacca Strait and the South China Sea. This underscores the critical significance of this sea route for the Chinese economy as the primary maritime line of communication.

A Dramatic Map

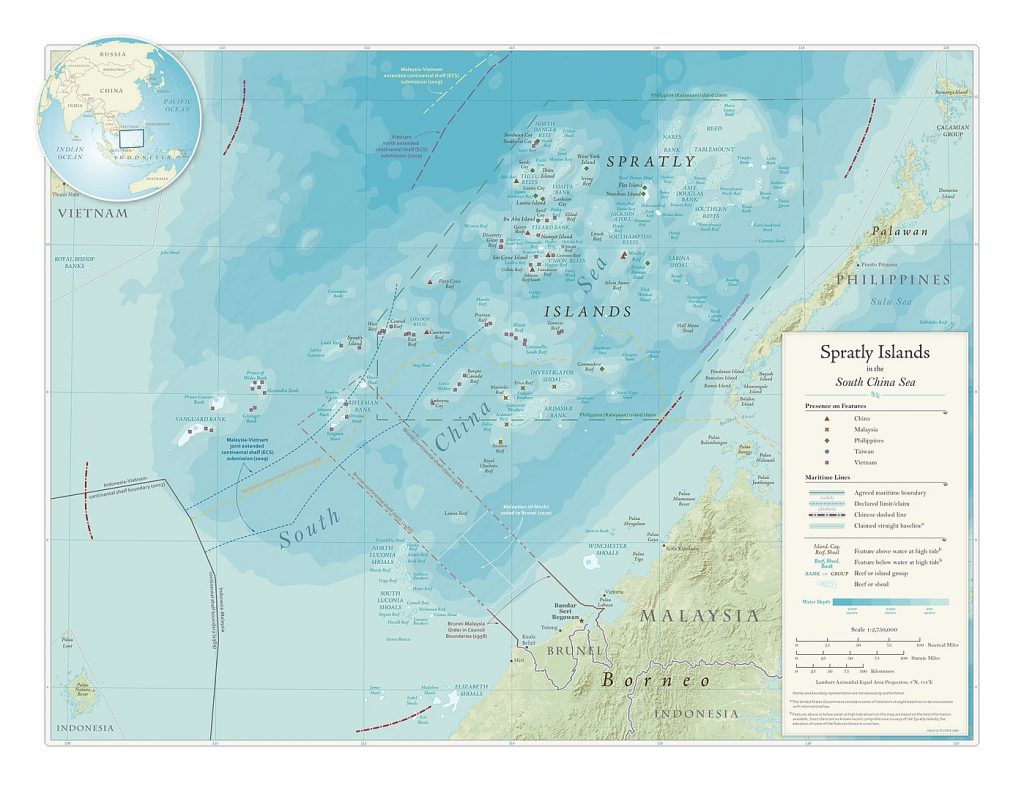

Tension rose this year August, when the Chinese government released the officially recognized map of the country (“The 2023 Edition of the People’s Republic of China Standard Map”). The map reaffirmed Beijing’s territorial claims to Taiwan, the bordering Arunachal Pradesh province belonging to India, and the majority of the South China Sea. India protested against this move, and countries involved in the longstanding territorial dispute in the South China Sea, namely Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, expressed their objections, while Brunei did not respond.

The 2023 Edition of the People’s Republic of China Standard Map

An interesting feature of the released map is that a territory belonging to the Russian Federation is now also “transferred” to China. This is because, as per the agreement reached between the two countries in 2008, the Great Ussuri Island, situated on the Amur River, was depicted entirely as part of China. Moscow has not officially responded to the new map yet. Lately, the debate over territorial claims related to the South China Sea seems to be escalating, casting a shadow on improving Sino-Vietnamese bilateral relations. Just a few weeks before Hanoi’s mentioned protest, Vietnamese authorities banned the film “Barbie” because it briefly featured a map that, according to China’s perspective, depicted the South China Sea. The Philippines’ objection is less surprising, as Manila has recently leaned decisively towards Washington, allowing the establishment of new American military bases in its territory. Meanwhile, the annual two-week joint Indonesian-American, “Garuda Shield” military exercise has begun in September, at the peak of the tension. A total of six participated; in addition to the two “founders,” Japan, Singapore, Australia, and the United Kingdom were also involved.

It is worth noting that in recent years, the territorial dispute between Indonesia and China has reignited as Jakarta began drilling in the southernmost tip of the South China Sea.

The root of the dispute lies in Indonesia’s claim to fishing and mining rights within its internationally regulated 370-kilometer exclusive economic zone from the Natuna Islands, which extends into the part of the South China Sea claimed by China. While Beijing recognizes that the Natuna Islands are part of Indonesia, it does not accept the extension of the exclusive economic zone associated with the islands, as it considers the portion overlapping with China’s claims in the South China Sea as its internal waters.

Negotiations have been ongoing since 2017 between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and China for the development of a Code of Conduct aimed at resolving the South China Sea dispute, but so far, there has been little progress. The increasing frequency of tensions in recent years may be related to the stagnation of the negotiations, and the diminishing hope of reaching an agreement is increasingly driving the involved parties to more direct assertion of their interests. The tension is expected to escalate if there is no progress in the development of the Code of Conduct.

Peacemaker or Warmaker?

The potentially destabilizing conflict in Gaza began in this atmosphere – no wonder that one of the significant questions for the coming year is whether the conflict will spread to the South China Sea. Beijing is trying to leverage the conflict in Gaza, aiming to further strengthen its mediator role in the region. Chinese top diplomat Wang Yi has discussed the promotion of peace with his American, as well as Israeli, Palestinian, and Iranian counterparts. However, Western analysts warn that Beijing lacks sufficient influence in the region, emphasizing that – similar to the conflict in Ukraine – the crisis in Gaza can be seen as a frozen conflict.

The spillover phenomenon also includes the fact that while remote armed conflicts pose an escalation risk, their resolution does not necessarily reduce tension. The militarization of the South China Sea has been ongoing for years, with various military bases displaying different sovereignty markers proliferating in the region.

Gradually, China is expanding its presence in the South China Sea since early 2010’s. As per satellite images provided by the US data company Planet Labs, Beijing has initiated the construction of new infrastructure on a small island within the Paracel archipelago, situated to the south of the Chinese island of Hainan and east of the Vietnamese coast. This region is claimed by both countries, although China has exercised de facto control since 1974. The images reveal the development of a runway on the island, in addition to a cement factory, enhancing Beijing’s projection capabilities in an area where it asserts almost complete sovereignty, extending into the exclusive economic zones of neighboring countries. The discreet continuation of the construction and militarization of islets in the South China Sea, initially revealed in 2015, persists alongside more overt actions.

An Alliance of Anger

Vietnam’s Defense Ministry announced in August, that the country intends to strengthen its military position on the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, an area where territorial disputes with China and the Philippines persist. The proposal, expected to cost around 6.4 trillion dong ($270 million), allegedly involves activities such as dredging and landfill operations to establish space for a substantial dock. Additionally, it encompasses enhancements to missile and anti-aircraft installations.

The Spratly Islands in the South China Sea (Source: United States Department of State Cartographer / Wikimedia Commons)

After a yearlong tug of war with China, the Philippines now calls for other countries taking part in joint patrols in the South China Sea. The announcement comes a week after conducting such operations with the U.S. and Australia, Defense Secretary Gilbert Teodoro told Nikkei Asia in an interview. Less than a week before, the Philippines and Australia initiated their inaugural joint sea and air patrols in the South China Sea, after Manila also engaged in similar actions with the United States.

As more countries in the region increase their military presence, an increasing number express concerns due to the United States’ position. The Biden administration has doubled the number of American armed forces in the Middle East while making political commitments to the ongoing war in Ukraine. Despite warnings from experts that Washington is overextending itself with a three-front (Ukraine, Middle East, Indo-Pacific) presence, the official narrative maintains that the United States will not abandon its allies in East Asia. In November, General Charles Brown, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff confirmed to the press: The U.S. response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas war will not impede its military’s ability to counter China.

[…] to the original question: is the Taiwan issue exciting at all? The nature of the Cross-Strait conflict clearly reveals that exhaustion is the primary tactical elements. It’s a nerve-wracking mindgame, […]

[…] as well. More weapons may cause accidents and incidents. For example, the weapons floating in the South-China Sea can go out of control,” Siemon Wezeman, the Senior Researcher of Arms Transfers Programme at the […]

[…] and continued to supply weapons to the Kiev government. Indonesia’s main security issue is the South China Sea disputes, in which Jakarta is not a […]

[…] especially in politics. Political dynasties, ranging from Thailand to Indonesia, highlight the region’s inability to establish strong and functional institutions. The heirs of these families are often […]

[…] based not only on interests but also on values. She emphasized that the Alliance must adapt to a changing environment. “We live in an increasingly interconnected world, where instability can occur in our […]